Clarence B. Jones in The Baddest Speechwriter of All. Photo: Courtesy of Brandon Somerhalder/Breakwater Studios

Clarence B. Jones doesn’t have to wonder what the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would say in this moment.

He knows.

“He would say, ‘Stay the course. Commit yourself to nonviolence,’” Jones says.

“And he would pull me aside. He’d say, ‘Now I know, Clarence, that’s a challenge for you.’”

He means the nonviolence part. Jones, 95, could never be accused of not staying the course.

More than 60 years after working with King as a speechwriter, lawyer and political adviser at the height of the civil rights movement, he continues to honor his friend’s legacy of leadership in the fight against discrimination.

“We’re going through some very difficult times,” he tells New Jersey Monthly in an interview just hours after a Border Patrol agent shot and killed Alex Pretti, a 37-year-old intensive care unit nurse exercising his First Amendment rights in Minneapolis.

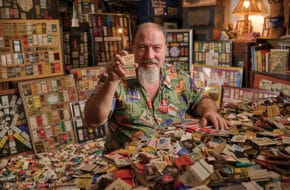

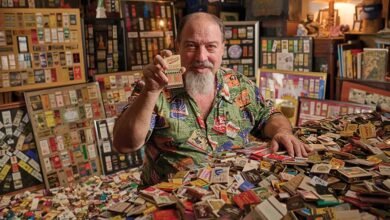

Jones, who spent his early life in South Jersey, is the subject of The Baddest Speechwriter of All, a new documentary short now screening at the Sundance Film Festival and available to stream online this week. On Tuesday, it won the Grand Jury Prize for Short Film.

NBA star Stephen Curry, making his directorial debut, teamed with Oscar-winning filmmaker Ben Proudfoot to tell Jones’ story of how he came to work with King. Interviews with Jones are joined with animated renderings.

“I cannot say enough words of praise about Steph Curry and Ben Proudfoot,” Jones says from his home in California. “They’re part of the best of our generation.”

Clarence B. Jones (center) with directors Stephen Curry (left) and Ben Proudfoot on the set of The Baddest Speechwriter of All. Photo: Courtesy of Bryson Malone/Breakwater Studios

Proudfoot won his latest Oscar for best documentary short for the 2023 film The Last Repair Shop. Co-directed by composer Kris Bowers, it follows some of the people who repair thousands of instruments for students at Los Angeles schools. Proudfoot won his first Academy Award for the 2021 documentary short The Queen of Basketball, about Lusia Harris, a trailblazer in women’s basketball and Basketball Hall of Famer. That’s how he met Curry, 37, who served as an executive producer on the film alongside Newark native Shaquille O’Neal. Curry introduced him to Jones, whom he considered a mentor and friend.

The Baddest Speechwriter of All zeroes in on decisive moments in a remarkable life, with a focus on key experiences that Jones shared with King behind the scenes.

“I was just blown away by the story,” Proudfoot, 35, tells NJM. “And then, of course, when I met Clarence, I was just amazed at his extraordinary storytelling ability.”

Curry sat down with Jones almost three years ago for hours of interviews. “It sort of stemmed from Stephen’s desire to pay tribute to this great man, and I was honored to meet him and fall in love with Clarence, as so many who meet him do,” Proudfoot says.

One highlight of the film is Jones describing his realization that a sizable portion of his own writing had made it into King’s landmark “I Have a Dream” speech.

Another is the moment Jones committed himself to King’s mission. It didn’t happen right away.

“I thought initially he was a spoiled, crazy Baptist preacher,” Jones says in the film.

He first got a phone call about King in 1960. A judge and friend told him that the Georgia preacher, known for his role in the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama, had been indicted for tax evasion. Jones assumed that King hadn’t paid his taxes, though his friend believed the minister was telling the truth. He said he wouldn’t go to Birmingham to offer his legal services.

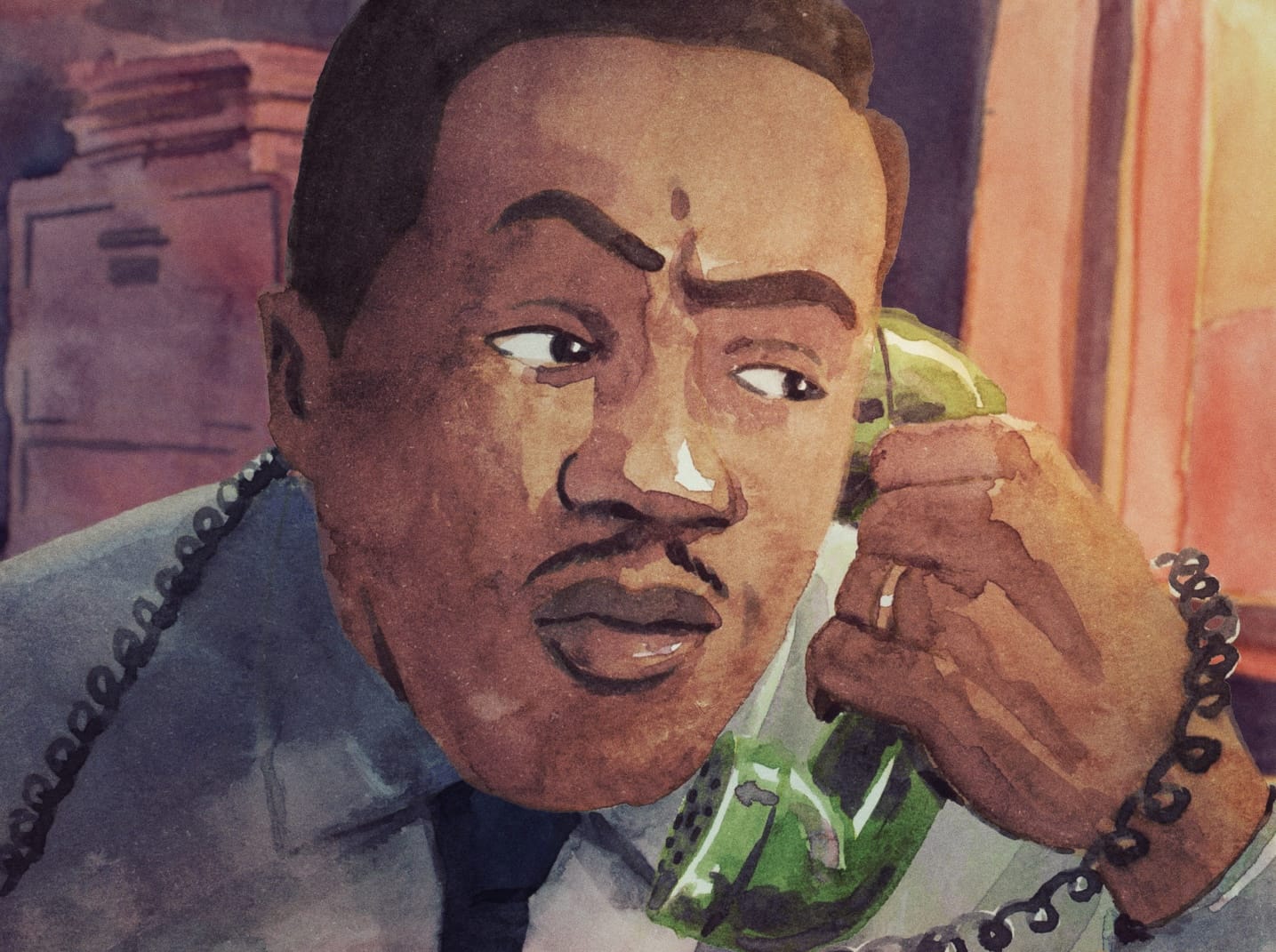

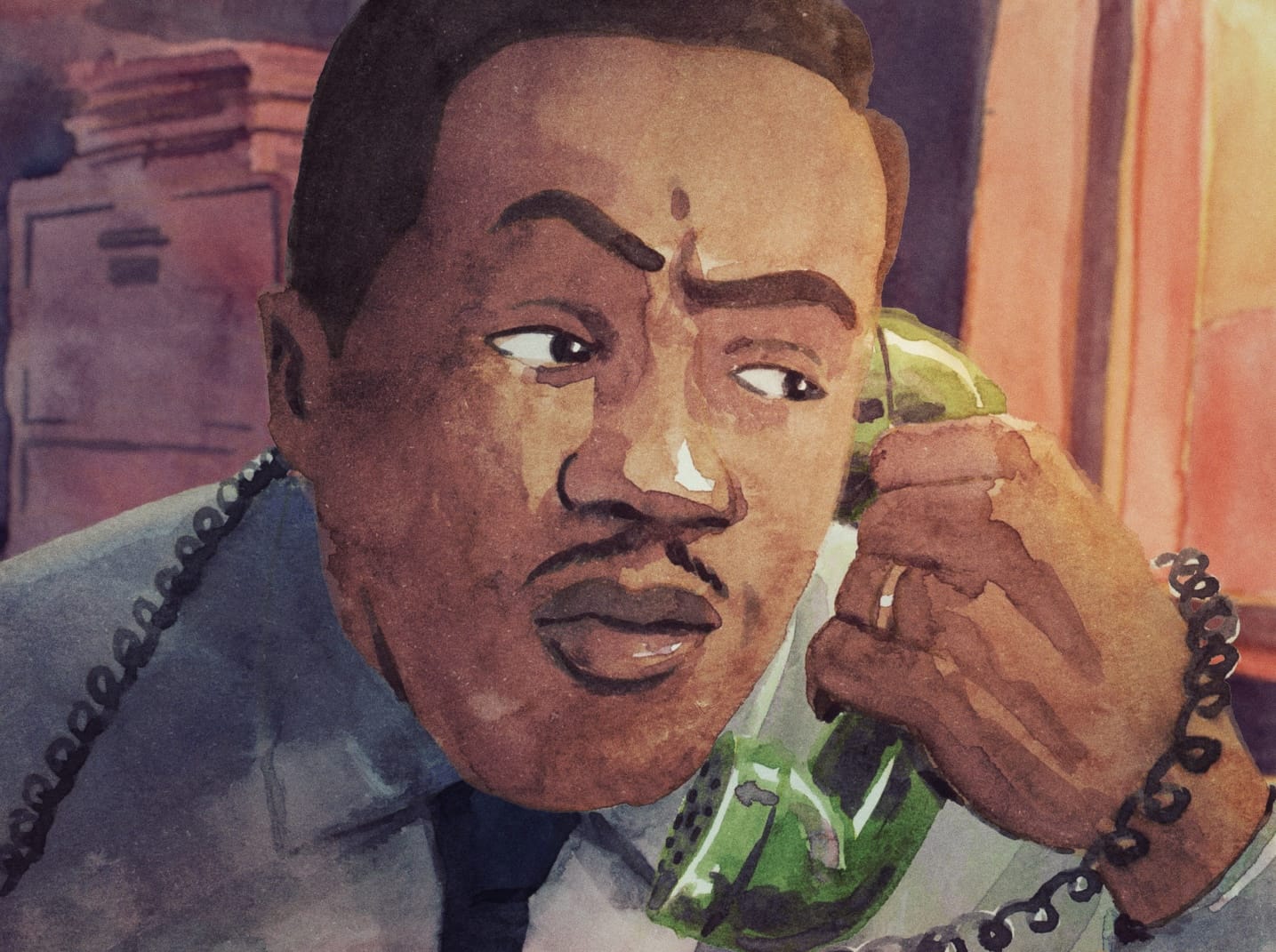

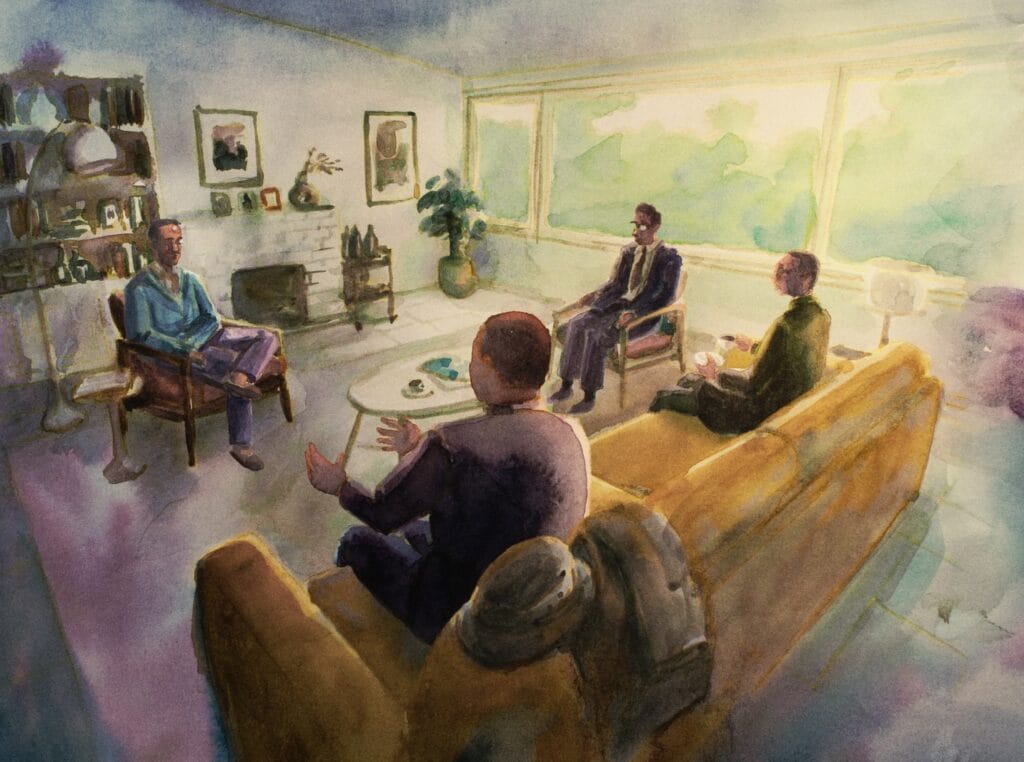

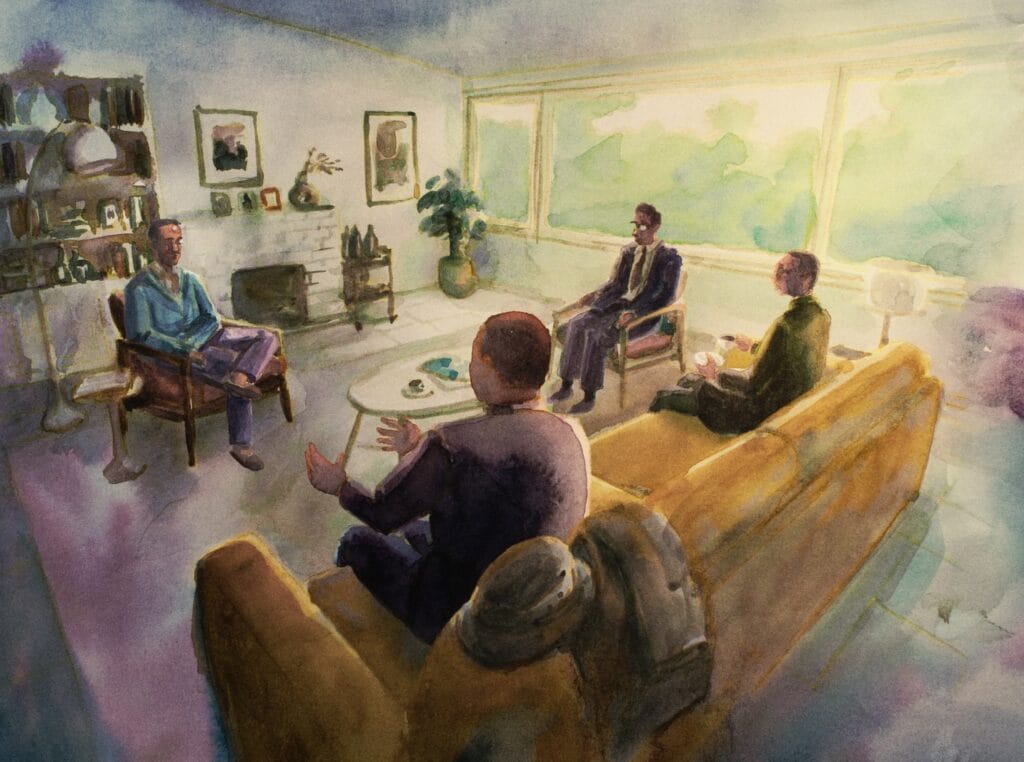

An animated rendering in The Baddest Speechwriter of All. Courtesy of Daniel Bruson/Breakwater Studios

But the next day, Jones found that he couldn’t avoid King, since the civil rights activist was in California. Soon, the man himself was at his doorstep. But again, Jones said he could not help. “Just because some preacher got his hand caught in the cookie jar stealing, that ain’t my problem,” Jones told his wife.

However, he did accept an invitation to hear King preach at a church in Baldwin Hills, California. What happened next would change the course of his life in ways that continue to reverberate through history.

It was Jones’ first time witnessing King at the pulpit. He would come to see him as a “great instrumentalist.” And he would know, because his own life was never one-note.

Jones, who grew up in East Riverton, a part of Cinnaminson Township in Burlington County, is also a clarinet player who studied at Juilliard when he was still in high school. Later, he worked in the music industry as a copyright lawyer. “I used to be what we would call a motherf—er,” he says in the film. “I was a bad dude.”

And King? “The baddest dude living this side of heaven.”

Sure, Jones had played music for years, but King was the one who got him to really wake up and listen, he says—to embrace a higher purpose. And when he heard King that day at the church, he definitely heard music.

“I guess I have a gift, and that gift is I have a very good audio memory,” Jones tells us. “I hear words different than most people…It comes out both as a word and as a musical note.”

When King delivered speeches and sermons, his voice was like the music of “Charlie Parker or Pablo Casals or Andrés Segovia,” Jones says in the film. “Or you when you shoot three-pointers,” he tells Curry, the star point guard for the Golden State Warriors. “That’s perfect pitch, brother.”

Jones watched as King moved the people in the church with his delivery. Then he started talking about a young lawyer in the audience. Jones, realizing he was the very same person, tried to make himself small in his seat. King proceeded to quote a 1922 Langston Hughes poem.

Jones saw what King was doing. He’d told him that his parents had worked as domestic servants. The Hughes poem King chose was “Mother to Son.”

“Well, son, I’ll tell you:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor—

Bare.”

Jones, picturing his own mother, began to cry. When the service was done, Jones had a question for King: “When do you want me to come to Birmingham?”

It wasn’t long before King was found not guilty of tax evasion.

A South Jersey foundation

Jones thinks of the place he grew up, East Riverton in Cinnaminson, as a To Kill a Mockingbird-type community.

It was a “beautiful, wonderful place,” he says, and he has fond memories of his childhood just across the Delaware River from Pennsylvania. The town is about half an hour outside Philadelphia, where he was born.

“That community, it’s idyllic,” Jones adds. “It’s almost like a fairy tale, like it doesn’t exist anymore…There was a lot of love and affection and respect that existed between the so-called colored or Negro community and white community.”

But in the film, he also recalls an incident from his childhood when he went to buy candy and was suddenly surrounded by white boys on bikes, who called him the N-word and other racial slurs.

He recalls his mother’s response: she asked him to look in the mirror, then told him that the person he saw was the “most beautiful thing that God has created.”

Jones’ parents worked for the powerful Lippincott family—his mother was a maid and cook, and his father was a chauffeur and gardener. When he tried to help out and wash a dish for his mom, she wouldn’t let him. She wanted something different for her son than a towel in his hand. “The only thing I ever want to see in your hand is a pencil and a dollar bill,” she told him.

Jones was sent to a Catholic boarding school in New England. Though he wanted to stay with his parents as a child, he would later see why they made that choice. “I owe everything that I am today to my mother and father,” he says. “They raised me with love and respect.”

Returning to New Jersey, he attended Palmyra High School, where most of his peers were white. He was first clarinet in the New Jersey All-State Orchestra and graduated as valedictorian in 1949.

In 2017, he returned to Palmyra High for the dedication of the Dr. Clarence B. Jones Institute for Social Advocacy.

“It means a great deal to me because it reflects the collective sentiment, the collective feeling of the community toward one of its own,” says Jones, author of What Would Martin Say? (2008), Behind the Dream: The Making of the Speech that Transformed a Nation (2011) and Last of the Lions: An African American Journey in Memoir (2023), which recently had an audiobook release.

“I want to send a special salute to all of my friends in New Jersey who still think of me, and I hope I’ve honored them along the way.”

The speech and the dream

As one of the only Black students at Columbia University, Jones unexpectedly found common ground with Jewish students and even picked up some Yiddish. (Later, at civil rights demonstrations, he would ask white people why they were there. One answer he’d often hear was that their grandparents died in the Holocaust.)

After graduating in 1953, he was drafted into the Army, and was stationed for almost two years at Fort Dix, then studied law at Boston University. He went on to work for Revue Productions (later part of Universal Studios) as associate general counsel, and found stability in entertainment law. He had a comfortable life.

When King presented him with the chance to join the movement, comfort became less of a priority amid the bright light of purpose.

When Jones was still a student at Columbia, his mother was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. After her death, a note was found under her mattress. In that note, she told her son she knew he’d grow up to be a “very great man.” Jones felt that greatness in his work with King.

He was the lawyer who, during King’s incarceration, transported the written-on scraps of newsprint and paper that became Letter from Birmingham Jail. He was not involved in crafting sermons, but King trusted him to write speeches. “If you’ve got somebody who has a musical background becomes a speechwriter, you’ve got the baddest speech writer of all,” Jones says in the film. “So when I was writing words it was like writing musical notes.”

King delivered some of the most famous words Jones ever wrote during his “I Have a Dream speech” on August 28, 1963 at The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. After Jones and King had talked about ideas for the speech, Jones wrote some text for consideration on yellow paper. He never thought those very same words would become the first seven paragraphs of King’s address.

But there, in front of more than 250,000 people at the Lincoln Memorial, he heard them ring out verbatim as King’s unmistakable voice thundered with conviction: “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity. But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free.”

Jones was floored. “I really thought about all of those maids and cooks, all of those people who didn’t have an education, all of those people who didn’t have the PhDs, all of those people who dedicated their lives, who were such beautiful people,” Jones tells us. “And I must say, the people from South Jersey were those kinds of people.”

When Jones came up with another part of King’s speech, he thought about one particular scene from his own work with the movement.

The passage: “In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, Black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

The inspiration: Jones had collaborated with actor, singer and activist Harry Belafonte to raise money for the release of King and other activists and protesters who were arrested with him. They went to the Rockefeller family for help, so one day Jones headed to Chase Manhattan Bank, where New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and his brother David opened their vault. David gave Jones $100,000 (which would be about $1 million today). But before he left, he had to sign a promissory note saying the money would be paid back. This was an unnerving development for Jones—until he learned the Rockefellers would indeed be covering the cost.

“That is exactly what I was thinking about,” Jones says of his decision to use the promissory note as a metaphor in King’s speech.

But the name of the speech famously comes from King going off the written page to deliver what Jones in the film calls the “greatest jazz rip of all.”

“Tell ’em about the dream, Martin! Tell ’em about the dream!” gospel singer Mahalia Jackson shouted before King said the words that would become forever associated with his life’s mission.

“Something that was new to me was to learn that the famous ‘I have a dream’ refrain, and so many of those lines that have become so important in the canon of American history, were improvised by Dr. King, and were kind of spurred on by a spontaneous outburst,” Proudfoot says. “I just was amazed by that.”

Jones remembers King’s astounding transition toward the end of the speech. “It was almost a little bit biblical,” he says.

Witness to history

One of the most touching parts in the documentary is when Jones visits the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C.

Jones visiting the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, D.C. Photo: Courtesy of Brandon Somerhalder/Breakwater Studios

Approaching the 30-foot sculpture with the aid of a walker, he reaches out and touches his larger-than-life friend bursting from illuminated stone. Through animation, Proudfoot and Curry flash back to the day when Jones approached King in that California church. In the scene, he’s been crying, and he puts his hand on the minister’s shoulder. King hesitates then smiles, knowing he’s reached Jones.

The tender sequence, from Brazilian animator Daniel Bruson, is particularly emotional. Proudfoot says the filmmakers needed a way to illustrate Jones’ stories, since not many photographs of him are available from that time, given the private nature of his meetings with King. When Jones started talking about having a “mental picture” of his mother, the directors decided to go the animated route.

“Each frame is a hand-painted watercolor painting,” Proudfoot says of Bruson’s work in the film. “I think it’s one of the most visually compelling animation accompaniments to a documentary I’ve seen.”

Courtesy of Daniel Bruson/Breakwater Studios

Jones was moved by the heartfelt illustration of chapters from his life. “Here I’m 95 and supposed to be a hard-ass guy, right? Even I started to cry when I saw it,” he says with a laugh.

Jones, who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Joe Biden in 2024, will soon be approaching his 100th birthday, but Proudfoot is struck by another reality of time: King’s rise was a relatively recent development.

He remembers how in the first afternoon of filming, Jones called him “Martin.” For the director, hearing that simple distinction dissolved the remove of history, the kind reinforced by black-and-white footage. “This was his friend,” Proudfoot says. “It was his colleague…It just kind of immediately brought it home for me that this was not that long ago.”

As the film reaches audiences at Sundance and beyond, Jones remains connected to his dear friend through his life’s example.

“I ground myself with what Martin King said and what he believed in,” he says. “You have to love the people you serve. You can’t fake it. You have to care about people.”

Jones thinks about the length of his life. “I’m here—why?” he asks in the film. Why is he a nonagenarian when his celebrated friend, assassinated in 1968, didn’t make it to his 40th birthday?

He is a witness, he says.

“I’m here to tell the story.”

The Baddest Speechwriter of All is currently screening at the Sundance Film Festival as part of the documentary short film program, which can also be watched online through the festival from January 29 through February 2.