ISTANBUL (RNS) — Pope Leo XIV is set to touch down in Istanbul at the end of November before visiting Lebanon for his first international trip since his papal election in May. The pontiff will visit eight cities from Nov. 27 to Dec. 2, sitting down with both political and faith leaders and leading Masses for Catholic locals and pilgrims.

Though Leo will first meet with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and various religious leaders, one of the most significant aspects of his visit will be joint ceremonies with Bartholomew I, ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople and one of Eastern Orthodox Christianity’s chief spiritual leaders.

The two together are slated to visit the Turkish city of İznik, once Greek-speaking Nicaea that 1,700 years ago played host to the first ecumenical council. There, early church fathers determined some of Christianity’s most basic doctrines, such as setting the date of Easter, explaining the trinity and clarifying the divinity of Jesus. It was agreed that Jesus was “God from God, light from light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one substance with the Father,” as reads the Nicene Creed, which many churches hold to be the fundamental declaration of Christian faith.

The anniversary of Nicaea isn’t just a historical moment. It’s a symbol around which ecumenically minded leaders in both Orthodox and Catholic churches have continued to work on bridging the centuries-old divisions between the churches.

The pope and patriarch standing together at Nicaea has been in the works for some time. Luca Refatti, an Istanbul-based Catholic priest, told RNS the trip was planned by Pope Francis but delayed by his sickness and canceled by his death earlier this year. That it was chosen for Pope Leo’s first apostolic international trip is a signal he will follow in Francis’ footsteps in bridging relations with other churches, Refatti said.

“To celebrate this moment is important because it is reminding us of our unity,” said Refatti, who stressed that the First Council of Nicaea — which occurred only a few years after Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire — predates divisions of most modern churches. “Nicaea is important because it is basically the symbol, the creed, where every Christian is united. Now, Orthodox, Catholics, Syriacs, Armenians, everybody recognizes and accepts the creed of Nicaea.”

First Council of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey), A.D. 325, fresco, c. 1600. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

One of the longest-standing disagreements between the Orthodox and Catholic churches is the inclusion of a single extra word — “filioque,” meaning the son — in the Latin translation of the creed, and not found in the Greek version used by the Orthodox churches.

However, building relations with the Vatican isn’t something Bartholomew has shied away from since his enthronement in 1991. Samuel Noble, a scholar of Orthodox Christianity at Belgium’s University of Liège, said 1960s Patriarch Athenagoras served as an example for such cooperation.

“Patriarch Bartholomew and a lot of the leadership in Fener (Turkey) still very much hold up the example of Patriarch Athenagoras as sort of the ideal Patriarch of Constantinople,” Noble said.

In addition to this year being the 1,700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea, November will be 60 years since the formalization of the Second Vatican Council, when Pope Paul VI and Athenagoras began the process of Catholic-Orthodox reconciliation.

“After the (Second) Vatican Council, the prospect changed completely,” Refatti said. “It turned from, let’s convert the heretics, to let’s build together unity.”

Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew speaks during the Advancing Human Rights and Social Progress session at the Concordia Annual Summit, in New York, Monday, Sept. 22, 2025. (AP Photo/Andres Kudacki)

Bartholomew has held that harmonious stance even when it has put him at odds with other leaders in the Orthodox world who have held more theological distance from Rome. “What seems to be quite on their minds in Istanbul is also the intra-Orthodox significance of this,” Noble said.

During a recent visit to Romania, Bartholomew downplayed the autonomy of more recently created patriarchates in the Balkans and elsewhere, some of whom have retained better ties with the Moscow patriarchate, which broke communion with Constantinople over its support for an autocephalous church in Ukraine.

But regardless of international and intra-church politics, for communities in Turkey, the interaction between two of Christianity’s most prominent figures is a welcome sign that reflects what’s already happening in many churches. Refatti said in Istanbul, there’s “a huge density of cooperation among existing churches.”

“We share spaces, we share sources, we pray together,” he said. “For most of the people on the ground, the people of God, they feel they belong to the same church. The difference between our church and the Orthodox world boils down to the authority of the pope.”

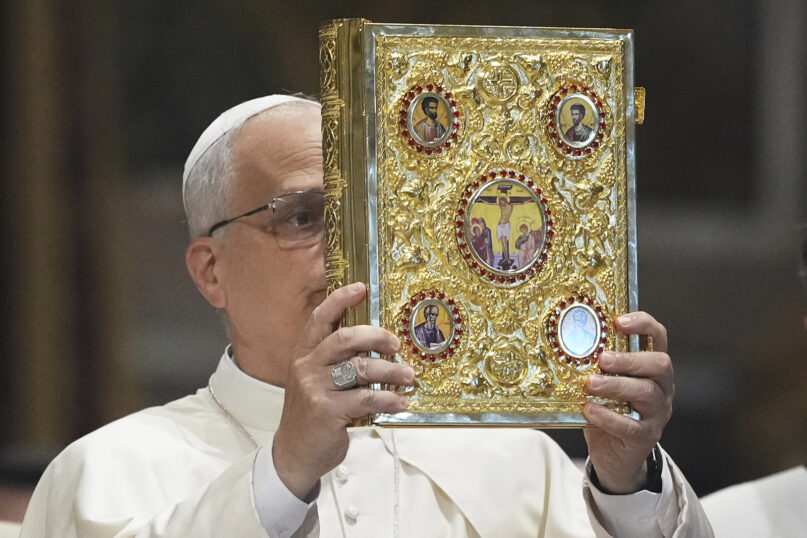

Pope Leo XIV holds the Gospel as he presides over the opening of the pastoral year of the Diocese of Rome in the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, Sept. 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

One symbol of unity many are hopeful to see — especially in Istanbul, where Orthodox and Catholic communities are in close proximity and include mixed families — is aligning the date of Easter. While the Greek Orthodox Church adopted the revised Julian calendar around a century ago, which aligned Christmas with the Gregorian calendar that Western Catholics and Protestants use, they still use a different algorithm to calculate the date of Easter, resulting in the dates being as far as a month apart depending on the year. This year, they happened to align on the same date.

In addition to the ecumenical overtures expected for the Turkish leg of the trip, the pope’s Lebanon visit is expected to give welcome attention to Christian communities facing war and persecution in the Muslim-majority country. The pope will “bring a message of peace and understanding to the heart of a Mediterranean area that has, for several years now, been in the midst of catastrophe,” said Claudio Monge, a Catholic priest who leads the Dominican Study Institute Istanbul.

In Lebanon, Christian communities have been impacted by the war in Gaza and Hezbollah’s conflict with Israel.

“(The visit to Lebanon) is highlighting his concern for a very endangered community and is a very big deal,” Noble said, adding that going to the country “seems to have been more (of Pope Leo’s own choice), rather than a continuation of something Francis was doing.”

Source link