WASHINGTON (RNS) — Pastor Jared Longshore isn’t exactly a holy roller preacher. Bearded and bespectacled, his sermon before the D.C. plant of Christ Kirk church on Sunday (July 13) was delivered in the subdued, heady style typical of the often buttoned-up Reformed Christian tradition.

But as Longshore stood underneath an American flag suspended just above his head, its stars and stripes facing toward the floor, the pastor made clear that the new congregation — an outpost of an Idaho church run by a self-described Christian nationalist — wanted to make some noise.

“We understand that worship is warfare,” Longshore said, leaning over the lectern. He paused for a moment, then added: “We mean that.”

Many in the roughly 120-strong congregation nodded in agreement, a few fanning themselves with church bulletins as they sat packed together in the small, non-air-conditioned room just a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol. And the message appeared to resonate with the most notable attendee among the crowd of worshippers: U.S. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth. Children in the pews whispered excitedly when Hegseth entered, and the defense secretary was mobbed by supporters as he left the church.

While the service itself followed the traditional rhythms of Reformed Protestant liturgy — confessions of faith, Scripture readings and hymns sung in harmonies that emphasize fourths and fifths — Longshore’s sermon was full of political references. He lauded the Department of Government Efficiency and argued that liberty and equality are concepts that only make sense if they are attached to conservative Christianity.

“If you get rid of God, you lose all sense of what equality is,” Longshore said.

Pastor Jared Longshore. (Video screen grab)

The church plant is the latest example of pastor Doug Wilson’s growing sphere of influence among a cadre of conservatives sometimes described as the “New Right.” Having founded Christ Kirk (also known as Christ Church) in Moscow, Idaho, decades ago, Wilson has since helped establish a small denomination — the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches — while also creating a Christian school, college, seminary and printing press. Along the way, the stridently conservative pastor has sparked a number of controversies, from his blatant use of anti-LGBTQ+ slurs to his comments downplaying the atrocities of American slavery.

But Wilson’s political rise is more recent, tied mostly to his congregation’s headline-grabbing protests against pandemic restrictions and the pastor’s fervent, unapologetic embrace of Christian nationalism on his various YouTube channels. The result has been a flurry of prominent politically themed speaking engagements in the past two years, such as speaking alongside Russell Vought (who would go on to be the director of the Office of Management and Budget) at an event hosted in a U.S. Senate office building; addressing the crowd at a Turning Point USA conference; or speaking on a panel at the National Conservatism Conference.

Hegseth, who has praised Wilson’s books, said he moved to Tennessee specifically to enroll his children in a school associated with the Christian education movement popularized by Wilson. He also became a member of a local CREC church in the area. In May, Hegseth had his pastor, Brooks Potteiger, lead a prayer service at the Pentagon.

In an interview with Religion News Service, the Idaho-based Longshore — who is one of many pastors associated with Christ Kirk and the CREC slated to preach to the D.C. startup until it installs its own pastor — dismissed the idea that the church was part of an effort to influence D.C. politics in an explicit sense. He echoed Wilson, who has said the nation’s capital is now home to many members of the CREC denomination, and denied that Hegseth had any role in bringing the church to Washington.

But Wilson has also stated publicly that establishing the church is part of an effort to capitalize on “strategic opportunities with numerous evangelicals who will be present both in and around the Trump administration,” and Longshore acknowledged the effort is designed to be an indirect form of politicking.

“We do believe that culture is religion externalized, always, whatever the religion,” said Longshore, who serves as an associate pastor at Christ Kirk Moscow. “And politics is downstream from culture, and culture is downstream from worship.”

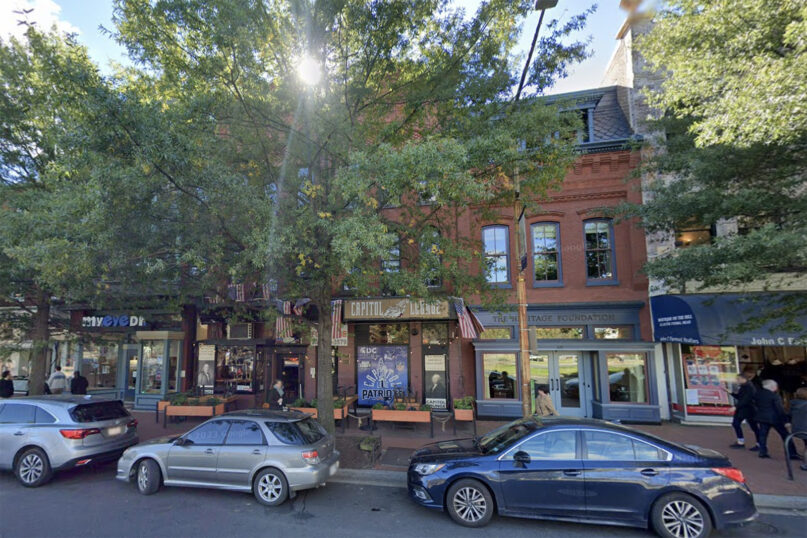

Christ Kirk DC met in a building, center, on Pennsylvania Avenue owned by Conservative Partnership Institute in Washington. (Image courtesy Google Maps)

Photographs were prohibited as a condition of being able to observe the service, but political symbols filled the worship space. Old newspaper articles praising Ronald Reagan dotted the walls, as did multiple American flags. Some ensigns were associated with the political right, such as the Revolutionary-era “Don’t Tread on Me” flag popularized among conservatives by the Tea Party movement. An “Appeal to Heaven” flag — another Revolutionary-era banner that has become associated with Christian nationalism and the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol — was draped on the wall nearby.

Granted, the room wasn’t decorated by the church itself, but rather, the flags were likely an artifact of the church’s political ties. The building, situated along Pennsylvania Avenue just southeast of the Capitol, is one of several owned by a far-right think tank known as the Conservative Partnership Institute. CPI is deeply connected to the MAGA movement: led by former U.S. Senator and Heritage Foundation head Jim DeMint and President Donald Trump’s onetime chief of staff Mark Meadows, the group’s partner organizations include the Center for Renewing America, which was created by Vought, and America First Legal, an operation co-founded by current White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller.

Christ Kirk’s own ties to the group appeared to extend to the pews: Spotted among the parishioners on Sunday was Nick Solheim, head of American Moment, an organization founded with the backing of then-Sen. JD Vance. The group is also listed among CPI’s partners.

Wilson’s various projects appear to be geared toward building a base of power distinct from others that have rallied behind Trump, such as Charismatic and Pentecostal evangelicals that surrounded the president during his first term. Wilson and his allies were openly critical of the president’s decision to install Pastor Paula White as head of his White House Faith Office, challenging her appointment in part because of their opposition to women’s ordination. And he has also shown a willingness to exert influence on other powerful, far-right religious institutions: Shortly after announcing Christ Kirk in DC, Wilson unveiled a similar effort at Hillsdale College, an influential religious school.

Christian nationalism is a mainstay of Wilson’s projects, a trend that continued on Sunday. Longshore stressed he believes “Christendom” has “marked this land from its founding.” He made a similar argument during his sermon, in which he also suggested that the U.S. has become a “fallen” or “lapsed” nation because it has drifted from its Christian roots.

A protester holds a sign outside the first service of Christ Kirk DC, Sunday, July 13, 2025, in Washington, DC. (RNS photo/Jack Jenkins)

It’s a common argument among purveyors of Christian nationalism. But it’s also a heavily disputed idea and one unlikely to sit well with D.C.’s deeply liberal population. Outside the building on Sunday, a pair of protesters stood jeering worshippers as they entered, with one holding a sign that read “Christ Church Is not Welcome.”

One of the protesters, who identified themself only as Jay, told RNS that Christ Kirk espouses values that are “fundamentally un-American” and “un-Christian.”

“But most fundamentally, they’re contrary to my deeply held values, and what I know are the deeply held values of D.C.,” Jay said.

The frustration was shared by at least one person inside the church. Nathan Krauss, who lives just outside D.C. and works in the federal government, said he attended the service as part of an ongoing personal effort to learn more about Christian nationalism. A United Methodist, Krauss said the service was fascinating in part because he found much of it unoffensive.

But he argued there was a clear disconnect between Scripture read by worship leaders and their support for Christian nationalism.

“I just really want to know: is the creation of this church going to create more liberty for the oppressed or less liberty for the oppressed? Because from everything that I see that they’re about, it seems to be that there’s going to be less liberty for people, not more,” Krauss said.

Longshore, for his part, said the hope is for Christ Kirk DC to evolve from a “service” of Christ Kirk Moscow to a mission church and, eventually, a “particularized church” with its own established local leadership.

Asked about the protesters, Longshore quipped, “We love it,” noting that Christ Kirk is sometimes protested in Moscow as well. Washington, D.C., of course, is a very different animal than Idaho. But Longshore argued that as a church leader preparing for “spiritual warfare,” he relished the challenge.

“What feels like crazy to you is actually normal stuff,” he said, referring to the protesters. “It’s like normal stuff from the land of the free, in the home of the brave. It’s what we used to be as American society, and what we still are, in large part, outside of the secular bubble.”

Source link