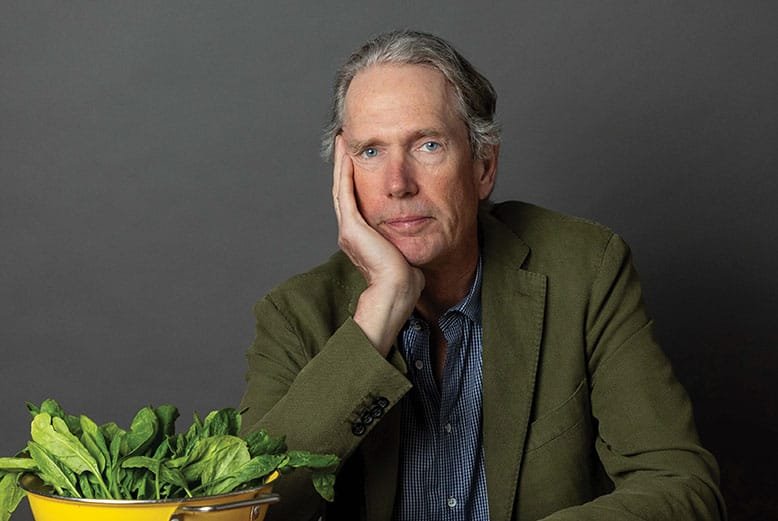

John Seabrook’s new book, The Spinach King, documents his family’s onetime empire. Photo: Erin Patrice O’Brien

Who knew that a vegetable farm in South Jersey was once the setting of intrigue, gangsters, celebrities and the Ku Klux Klan?

In The Spinach King: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty, author John Seabrook describes growing up in the leafy shadow of Seabrook Farms in Cumberland County and assesses his family’s influence on New Jersey and on his own life. “I was so little and didn’t know what was happening at the time when all this stuff was happening,” Seabrook tells New Jersey Monthly. “It’s a huge shock when you realize that maybe your parents aren’t really telling you the truth.”

In The Spinach King: The Rise and Fall of an American Dynasty, author John Seabrook describes growing up in the leafy shadow of Seabrook Farms in Cumberland County and assesses his family’s influence on New Jersey and on his own life. “I was so little and didn’t know what was happening at the time when all this stuff was happening,” Seabrook tells New Jersey Monthly. “It’s a huge shock when you realize that maybe your parents aren’t really telling you the truth.”

Among the hidden stories he unearthed about the farm, Seabrook found Klan meetings, tales of Hollywood starlet Eva Gabor, who skinny-dipped in the family’s pool, and rivers of alcohol.

The Spinach King is Seabrook’s fifth book, but it’s by far his most personal. “It was a lifelong project, and it’s about my life,” he says. “It’s a unique experience, you know—not like handing people just a book, but my life.” In the process of writing and researching the book, Seabrook discovered more ugliness than he had expected.

There was the 1934 strike by farm workers, to which his grandfather and uncles had responded with violence. There were financial dealings that skirted the edge of the law. There were lawsuit-related pre-trial interviews in which John Seabrook’s father described his grandfather as “an addict, a predator, and a paterfamilias who seemed to hate his own flesh and blood.”

HOW IT BEGAN

It all started when farming in New Jersey was a simple operation, with most crops driven to market in New York and Philadelphia the day they were picked. John Seabrook’s great-great-grandfather purchased 13 acres of farmland in South Jersey about a decade before the bucolic nickname “Garden State” was bestowed in 1876.

The first Seabrook was a failure as a farmer; when he died, no gravestone was erected. But succeeding generations built a farming and food empire that, at its height, provided about one-third of the nation’s frozen vegetables. Along the way, a series of Seabrook fathers and sons battled and betrayed one another, even as their family business depended on and profited from the image of a happy, healthy household at the heart of it all.

Seabrook Farms wasn’t simply an agricultural powerhouse. When Life magazine covered the enterprise in January 1955, the article described it as “the biggest vegetable factory on Earth.” At the peak of its success, Seabrook Farms sprawled over 50,000 acres and employed around 5,000 workers. The company’s frozen creamed spinach was the quintessential labor-saver for mid-century American housewives. As the farm became a brand, Seabrook writes, its reputation rested on “family, freshness and domestic modernity.”

C.F. Seabrook Photo: Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

The farm began to flourish when C.F. Seabrook, the author’s grandfather, bought out his own father (likely in a predatory deal) and then invested in and took advantage of advances in irrigation, quick-drying, and other technologies that allowed for vast improvements in production. C.F. studied how Henry Ford and other industrialists used both mechanical and social engineering to squeeze the highest possible profits out of a notoriously fickle business. It didn’t hurt, John Seabrook points out, that Americans in the 1910s were newly aware of the health benefits of eating vegetables, and those who had flocked to cities wanted to be able to eat lettuce and tomatoes, even though they no longer grew them at home.

A COMPANY TOWN

By 1920, C. F. had expanded his realm, forming a road-building company to create the transportation infrastructure needed for his crops to reach their expanding markets; in 1920, he was appointed as a New Jersey highway commissioner (and promptly awarded a top contract to himself).

Over the next several decades, Seabrook became more than just a major local employer; it was a company town, housing hundreds of workers and schooling their children (most of whom also worked in the fields). People who came to work on the farm included African Americans heading north for a chance to live outside the strictures of Jim Crow, Estonians fleeing a chaotic Europe under the Displaced Persons Act, and a large number of Japanese Americans who had been sent to internment camps during World War II.

Jack Seabrook inspecting plants on the farm. Photo: Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress

The author’s own father, Jack, had benefited from growing up a Seabrook, he writes. “He dressed in the finest British tailoring, served only the best French wines, and drove a stagecoach and four vanilla-colored horses along the country roads that ran through his Jersey estate, like an English duke.” He rubbed elbows with high society in Philadelphia and New York and dated actresses, including Eva Gabor. Jack Seabrook met his second wife (John’s mother) aboard the ship carrying Grace Kelly and her family to Monaco for her wedding to Prince Rainier in 1956. Dashing, wealthy Jack was a guest of the Kellys; his future wife, Elizabeth, was a newspaper columnist covering the event.

The actress Eva Gabor, who dated Jack Seabrook, with Seabrook Farms products. Photo: Courtesy of the Seabrook family

Then, in 1959, the year John Seabrook was born, his grandfather C.F. (who still owned a majority stake) sold the company to outsiders. “The major family cataclysm happened literally the year I was born, and then I kind of grew up in it,” Seabrook says. It inspired his writing. “It got me doing what I do, which is asking questions and figuring out insights.”

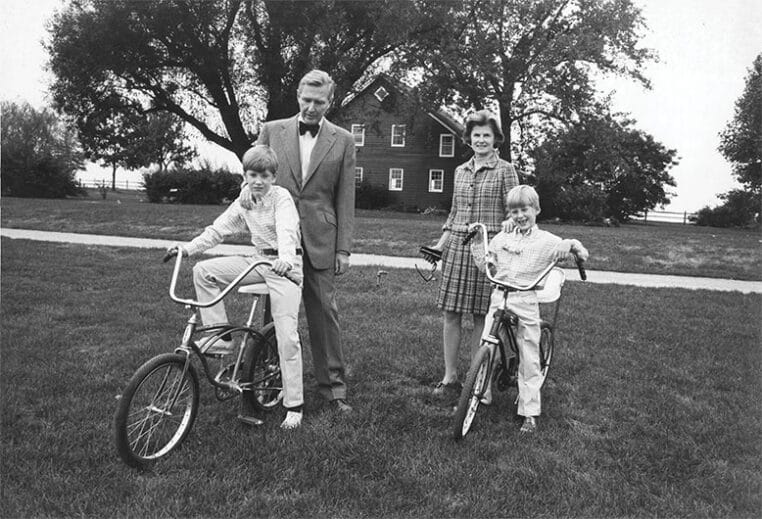

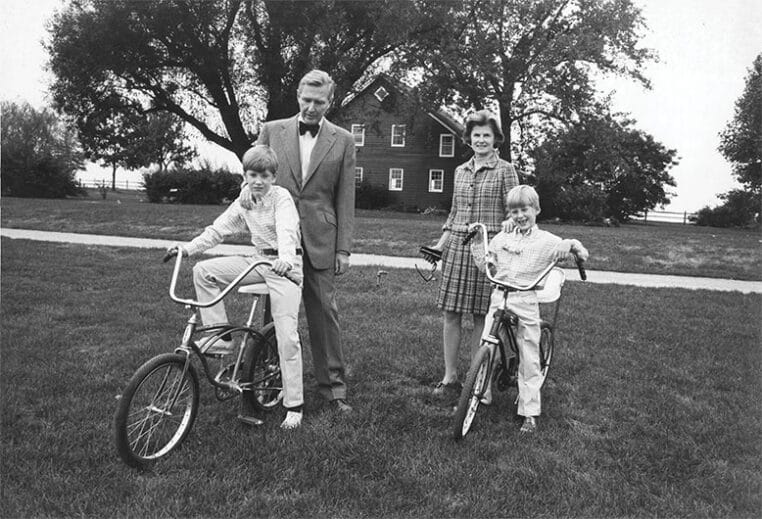

John Seabrook, left, with his younger brother, Bruce, and their parents in front of the family farmhouse in 1967. Photo: Courtesy of the Seabrook family

Growing up, he adds, everyone knew who he was because of his family name: “Everybody knew who the Seabrooks were around South Jersey, and a lot of people had worked for the Seabrooks at some point.” Over the years, starting at Princeton, where he studied creative writing with Joyce Carol Oates (the novella he wrote for her class convinced him he didn’t have the fiction gene), Seabrook knew that his family story was one he would have to write. But it took decades. “I basically came to it as a professional writer, and this story preceded me as a professional writer. It sort of shaped me.” Seabrook landed in magazine journalism at a time when it was flush with money and fun assignments. “It was incredible,” he says. “I went to South Africa. I went to Australia for Vanity Fair. You could fly business [class] if it was more than nine hours, no problem. I had an office. All that stuff is gone now. I was lucky.” He wrote his first big piece on his family’s story in 1995 for The New Yorker, where he is now on staff.

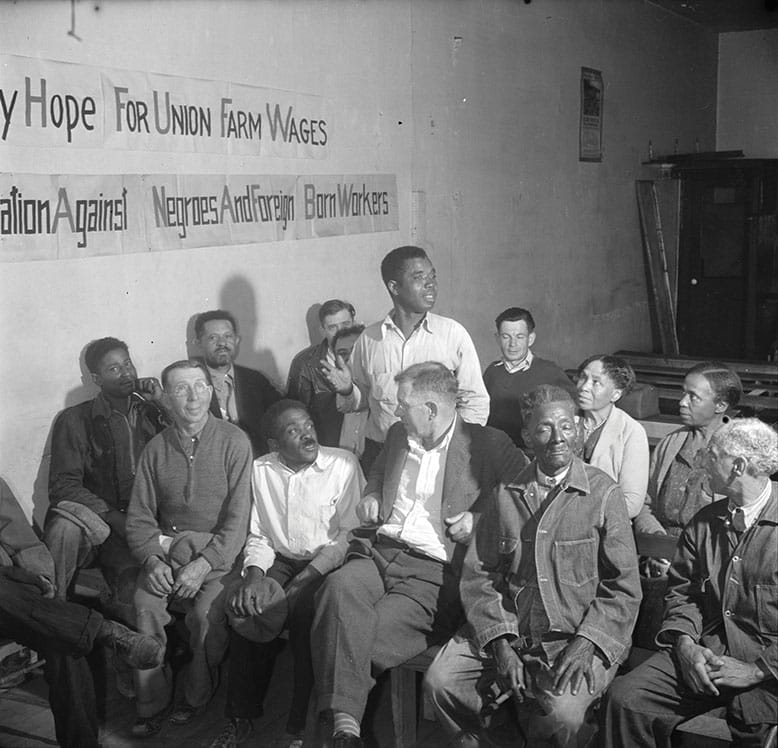

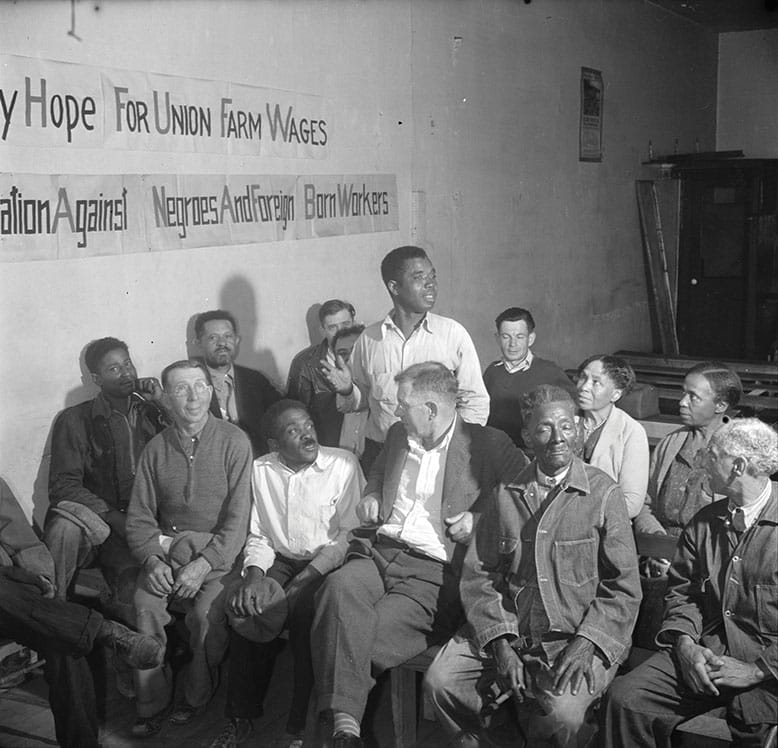

After helping his father deliver a speech at a reunion of Japanese American Seabrookers in 1994, John offered to research more family history for Jack’s planned memoir. What he found shocked him. First, there was the strike. In 1934, Black farmworkers protested their low wages and inferior treatment at Seabrook Farms. “Black and white workers lived in separate ‘villages,’” Seabrook writes, “an arrangement that was both ideological and political, because it allowed C. F. to play the different ethnic groups off against each other to keep control.” Not only that—workers considered “American” were housed in better facilities than those labeled white, but not “American,” such as Italians and other European immigrants. Black workers complained that they were laid off during seasonal slow times, while white workers were kept on.

GANGSTERS AND THE KKK

A Seabrook Farms union meeting in 1935. Gangsters and the KKK were brought in to break up a strike by the farm workers. Photo: Library of Congress

It all came to a head that summer. C. F. Seabrook sought to protect his business and family by bringing in a colorful gangster named Red Saunders as a watchman, and he armed his three sons, teenagers at the time. Also on their side: the local chapter of the White Legion, known for leafleting and burning crosses, and the local KKK, known for doing much worse. Fists and bombs were thrown. On a microfilm in the Bridgeton Public Library, Seabrook saw that his own uncle Courtney had been the driver of a truck that rammed people on the picket line, injuring four. A few days later, strikers and Seabrook came to an agreement, which C. F. broke immediately, firing 250 workers, most of them Black.

Writing about the strike ruffled family feathers. “I was supposed to be doing public relations for the family,” Seabrook writes, “not investigating it.” The more stories he pursued, the more he found, many of them embarrassing to his fellow Seabrooks, like C. F.’s bullying of his sons, his abuse of alcohol and pills, and his sexual indiscretions.

Farming is a seasonal business, and so is life. After publishing the 1995 New Yorker piece that caused family drama, John Seabrook mostly turned to other topics—his books’ subjects range from invention to business to the creation of hit songs—until taking on this one, the story of his family. Like many memoirists, he waited until both of his parents had died before finishing the book.

Photo: Erin Patrice O’Brien

“I think there were just certain things that I wouldn’t have wanted to really make public while they were alive,” he says. “Also, I just think when your parents die, if you’re a writer and you’re sort of something of a memoir writer, it’s a hugely freeing thing.” From his mother, a former journalist and tough critic of his writing, Seabrook got a strong warning not to write about family. “I think she knew that there was this stuff that happened that I didn’t know, that I was probably going to find out. I think it’s also partly that she was brought up as a journalist not to write about herself,” he says. Asked if she had been proud of his work at one of the country’s most prestigious magazines, he says, “Yeah, she was proud, but she was critical too.” (I asked if he thought his parents would have liked the book, or at least not hated it. “My father always liked publicity, so he would’ve liked quite a bit of it,” he says. “I don’t think my mother would’ve probably cared for it.”)

The women in the Seabrook family—the wives of C.F., Jack and John—played no official role in the family business. But in a scrum of ambitious and energetic fathers, sons and brothers who battled over control, they served as the dynasty’s “chief emotional officers,” Seabrook writes. As for himself, he married a woman he met in his early magazine days who’d never heard of Seabrook Farms and with whom, he writes, he “could raise children differently from the cold, best-foot-forward, stiff-upper-lip way that I was raised.”

Today, some of John Seabrook’s cousins own and operate a new version of the family business, now named Seabrook Brothers & Sons. Along with more than 100 offerings, they still grow, package and sell one of the legendary Seabrook products: frozen creamed spinach.

So how did five generations of farmers shape the writer John Seabrook? He didn’t inherit any of his ancestors’ business acumen, he says. “But I do love growing things, and if I had my druthers, I would probably live somewhere where I could spend more time growing stuff in a garden. Growing vegetables is something that I’ve always loved to do.”

Kate Tuttle is a writer and editor. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe.