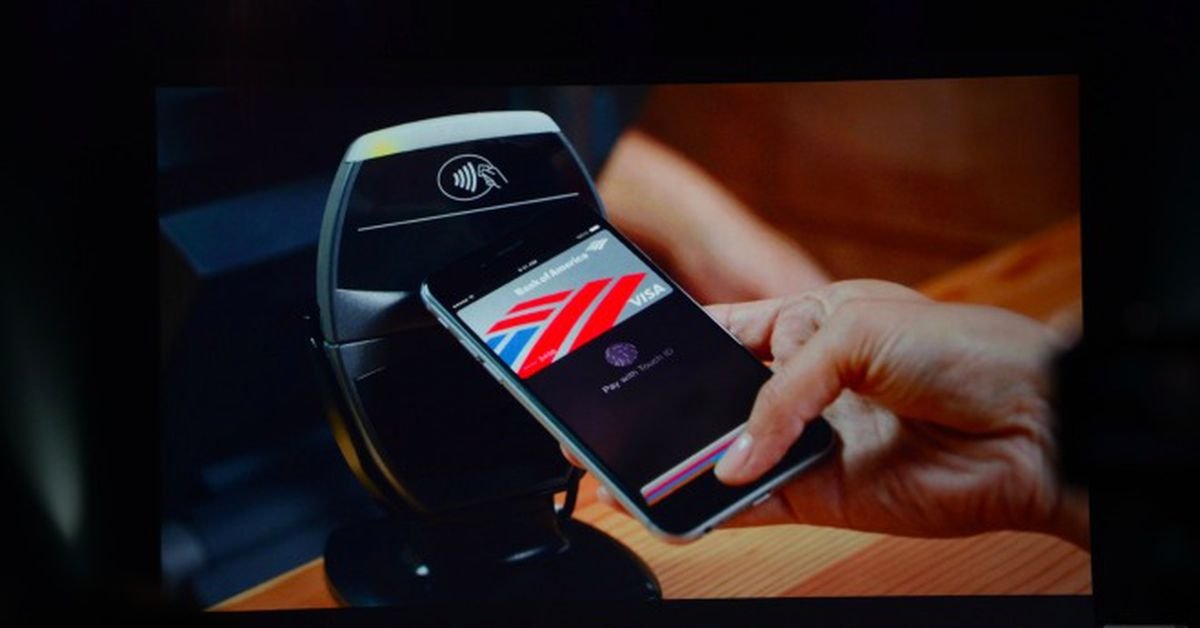

When Apple launched Apple Pay in 2014, at an event 10 years to the day before this year’s iPhone launch, Apple promised the feature would “change the way you pay.” The company didn’t just let you save a credit card number on your phone; it let you pay for things with a single tap by transmitting information through an NFC chip. Apple was so bullish on mobile payments that Apple Pay was even one of the key selling points for the also-just-announced Apple Watch.

A decade later, Apple Pay is everywhere. You can use it to buy groceries and coffee; you can use it to ride the New York City subway or rent a Lime scooter. You can use Apple Pay and skip the whole multipage checkout process on lots of online stores. You can use it on your phone, your watch, your computer, countless websites, your TV, and your headset. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau estimated that 55.8 million Americans made an in-store payment with Apple Pay in the month of April 2023. Apple says Pay works at more than 85 percent of retailers in the US, but anecdotally, I can’t remember the last time I couldn’t pay just by double-clicking the power button on my phone. Apple Pay is so good, it can be dangerous.

Apple Pay is one of the most Apple-y Apple products the company has ever shipped. It was, and is, a study in both the power of integration and Apple’s unique ability to get its way in a competitive industry. While Google flailed around with its own mobile payments system — which has been Google Wallet and Google Pay and Android Pay and I think Google Wallet again, and honestly who can keep track anymore? — Apple just relentlessly iterated on Apple Pay until it became both great and ubiquitous. It’s gotten a little bloated as Apple has looked for more ways to make it profitable: Apple Pay begot Apple Cash and the Apple Card and Apple Pay Later and Apple’s whole idea about digital ID cards, which have all worked somewhere between “kind of fine” and “not at all.”

And maybe most Apple-y of all, Apple Pay has been ruthlessly controlled and locked down by its creator. Other developers haven’t been able to access the tap-to-pay features, so you can’t pay directly from any app other than Apple Wallet. Developers have no other choice but to add cards to Apple Wallet (and thus pay the 0.15 percent fee for each credit transaction). You can’t change the app that appears when you double-tap the power button, either, not that you would, because nobody can build a competitive mobile wallet app without tap-to-pay. Have you ever noticed that there are no Apple Wallet competitors? They simply aren’t allowed to exist.

Apple has argued, as it always does, that these restrictions existed in the name of security and privacy, but critics say they’re actually about processing fees and platform lock-in. Apple Pay was even named as a core tenet of the US government’s antitrust case against Apple. “While Apple actively encourages banks, merchants, and other parties to participate in Apple Wallet, Apple simultaneously exerts its smartphone monopoly to block these same partners from developing better payment products and services for iPhone users,” the Department of Justice wrote in its initial antitrust complaint earlier this year.

Apple Pay is about to become the perfect test case for the future of Apple

A decade after its launch, Apple Pay is about to become the perfect test case for the future of Apple. After the antitrust case in the US and a series of new rules in the EU, Apple announced that beginning with iOS 18.1, third-party developers will be able to enable tap-to-pay transactions in their own apps. Users will also be able to set a default app for contactless payments and change what happens when they double-click the power button. There will be hoops for developers to jump through and fees for them to pay, but the chip will be available.

Opening up NFC access has the potential to turn tap-to-pay into tap-to-everything. For years, Apple and others have talked about wanting to turn all your keys, ID cards, loyalty cards, tickets, gift cards, and more into digital objects that you can transmit or share with a tap. Until now, that hasn’t really taken off, but many developers might now be interested in building these tools because they can build them into their own app. Banks and fintech companies might add tap-to-pay so you can pay from the same place you manage your money. Maybe you’ll be able to get into a bar, on a flight, into your car, or into your office with only a few taps. Maybe every file sharing system will support NFC, so you can tap your friend a photo or PDF. Maybe the NFC chip will become as core a part of the iPhone’s value as the GPS chip or the camera, the ongoing connection between your device and the real world. And maybe, because Apple has such cultural power within the tech industry, it will be the catalyst for digitizing these other systems everywhere.

Opening up NFC access has the potential to turn tap-to-pay into tap-to-everything

Or maybe opening up the system might ruin the whole thing. Maybe, instead of a single place with all your cards that appears anytime you press a button, you have to download, log in to, and manage every single payment option in your life in an entirely different app. Maybe some companies will support third-party wallets and some won’t, so you’ll have to remember that your Visa and AMC Stubs card are here but your Discover card and library card are over there. Maybe there will be huge security flaws in how all of these companies manage things, and companies will begin to collect vast amounts of data you’d rather not give them. Maybe they’ll stop supporting Apple Wallet — because processing fees! — and force you into their ugly, slow, ad-filled, upselling apps. Maybe Apple wasn’t just moneygrubbing and was, in fact, preventing the true moneygrubbers from making mobile payments unusable.

These are plausible outcomes, and there are some less extreme possibilities, too. But we’re about to see Apple confront this new world in so many ways: as the company is pressured to change its App Store rules, give developers access to previously unavailable system features, and allow users to pick more of their own defaults, the question is the same across every surface. Was Apple’s legendarily tight control about preserving user experience and making sure users got the best of everything with the least amount of work, or was it about Apple making its devices worse just to make them harder to quit? No one’s ever had a fair fight with Apple before. But the playing field is beginning to level.

Source link