Nick MacKinnon is a freelance teacher of Maths, English and Medieval History, and lives above Haworth, in the last inhabited house before Top Withens = Wuthering Heights. In 1992 he founded the successful Campaign to Save Radio 4 Long Wave while in plaster following a rock-climbing accident on Skye. His poem ‘The metric system’ won the 2013 Forward Prize. His topical verse and satire appears in the Spectator, and his puzzles and problems in the Sunday Times and American Mathematical Monthly. Email: [email protected]

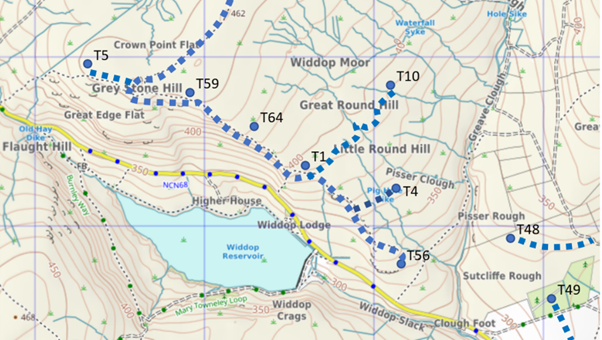

Turbine 56: Slack Stones SD 94170 32768 ///recall.compiler.hopes

15 August 2024 It is my first turbine walk since the end of the bird-nesting season, and I haven’t been so outnumbered by women in a social group since I was a teenage nurse at tea break, a boy among eight women. The doctors could smoke and work, but the nurses needed both hands for their patients, so by tea break they were gasping, and would pour the huge teapot with their left, reduce a Silk Cut to ash and pleasure in the right, and unpack their lives with a frankness that could strip the paint off a pine dresser. I still tuck hospital corners when making a bed and never use the spout handle on big teapots (which these days I only meet at funeral wakes) in case Staff Nurse Mackay calls me a jessie.

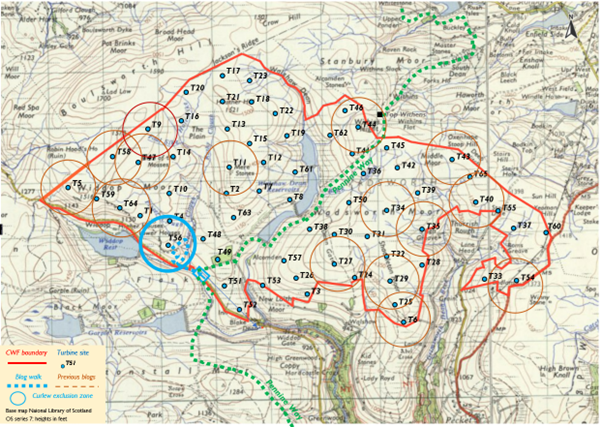

With the usual gang (Ali, Stella and Sheila) today, are artists Lesley Fallais and Shelley Burgoyne. We won’t get very far, but by the end of this blog we shall have a far clearer idea of what Calderdale Wind Farm Ltd are up to.

Shelley has cut her finger very badly while making sandwiches for the trip. Fortunately, Lesley arrived to pick her up and applied the entire contents of an industrial first aid box. I want to say the finger resembles the corpse wrapped in 42 layers in the current Sky documentary The Body Next Door. To stop myself saying that, I wonder instead if my companions know Sylvia Plath’s poem Cut:

What a thrill—

My thumb instead of an onion.

We are three miles from Plath’s grave in Heptonstall as the crow flies, but we can’t see the church from this low-lying site, which will want a 200-metre pylon.

Clive James, who was so good at writing about poetry because, relative to his ambitions, he was so bad at writing it, read Cut in London magazine in the winter of 1962, and said, ‘If she can do this, she can do anything.’ The poem finds at least seven images of American conflict from Mayflower to Cold War in the bandaged thumb: little Pilgrim; Redcoats; Whose side are they on; Saboteur; Kamikaze; Ku Klux Klan; Babushka.

Cut is six days older than me, written on the day of Khruschev’s letter to Kennedy, the High Noon of the Cuban missile crisis. If he received the codeword, my father was to leave his expectant wife in the fallout shelter under the stairs, draw a revolver from the armoury, and shoot anybody trying to get out of London on the A12. Babushka.

The heather is doing its thing. Although famous for massed shortbread-tin purples in the distance, the phosphor hallucinations close in are more striking, for heather has not evolved for our eyes (400-700 THz) but for honeybees (460 to 1000 THz) who are blind to red but can see well into ultraviolet. Is heather shimmer on our retinas the ghost of a world beyond 700 THz?

The permissive path that enters Lower Greave Clough is not easy to find from this end. When we were last here in the winter, coming the other way and with the scent of the tarmac ahead of us, we followed it easily, and Sheila found a dead crow and took it home, but now the grass and heather are high and we may never have been on the path before we had to cut left to the site. Although very close to the road, T56 Slack Stones is the least accessible of all the turbine sites for blade delivery. Once we stagger up, it offers an interesting view of the strange Widdop rocks.

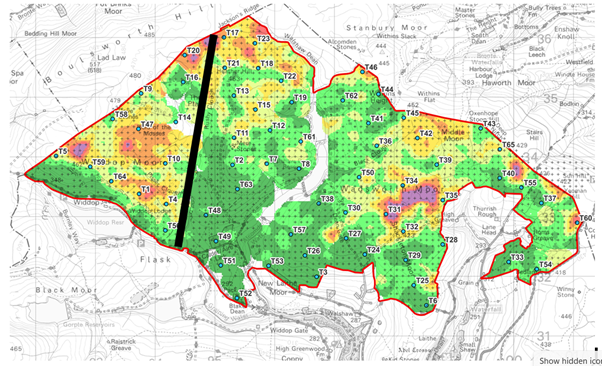

Muttley’s peat map has the site shaded light green, shallow for CWF, with a peat depth in the range 50-100 cm, so only back to the Battle of Hastings. It is raining, the walking is horrible and I have fallen over twice. We have only seen three grouse, haven’t really found a path, the way on looks bloody difficult, and as usual when we are at this western end, CWF seems ridiculous. Keeping out of my grumpy force field, Sheila found effortless beauty in this superb bog, seen in the next four photographs. Muttley finds this place only fit to be stripped down to boulder clay and filled with 350 tonnes of limestone to make a crane hardstanding.

Muttley’s limestone will be trucked forty miles, tipped on the Cock Hill Swamp compound, loaded into a dumper and carried past High Greave, Dean Gate, over Alcomden Bridge, up the east side of Greave Clough, over Foul Sike, past Dove Stones, across Crown Point Flat, up Grey Stone Hill, along the Scout past The Lumps and the Ravenstone and down the slope to the T56 Slack Stones, and thirty-five loads later a foundation for two tennis courts will have been constructed, right on top of the frog.

Right here at Slack Stones is where CWF seems at its most absurd.

The difficulties of getting a turbine blade to T56 become clearer when we try to find the path again so we can get into lovely Lower Greave Clough and finish a circular walk past Sutcliffe Plantation. In thick bracken somewhere near the sluices that grab the rainfall of western CWF and send it sideways into Widdop reservoir, we give up once each of us has measured our length in the bog. I catch up with Stella, who is being mildly ironical about Ali’s route finding. “Why have you brought us here!”

Stella has been talking to someone in the National Grid who thinks “CWF cannot be connected before 2038”. In trying to stand this startling claim up, I found the first cold facts about CWF since Deep Stoat told me the sole site entrance is on Cock Hill Swamp.

The scoping report submitted to Calderdale Council says this.

3.9. Grid Connection A connection offer has been received from the Electricity North West the District Network Operator (DNO) and an application to National Grid has also been sought as an alternative. Relevant surveys for these grid connection works will be incorporated into these work scopes. The connection via the DNO is currently proposed as two parallel 132 kV buried cables that will connect to the existing substation at Rochdale GSP. The scope of works for a connection to the National Grid transmission network has not been established at this point. The project is expected to instruct only one of the two options above.

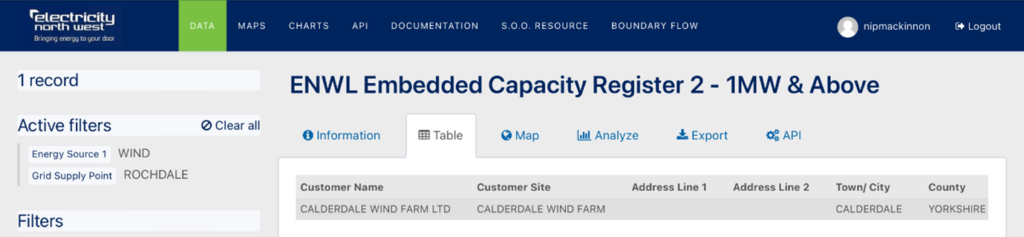

I started by looking for Calderdale Wind Farm on the Embedded Capacity Register for Electricity North West. This is a first-come first-served queue for generators who want to export to the grid, and developers who want to draw from it. You can register to read the document with just an email address, and there is an array of filters to help you navigate the large spreadsheet. Energy source: WIND Grid supply point: ROCHDALE is all you need to find the entry for CWF.

This is what the register says about CWF.

Customer: Calderdale Wind Farm Ltd, Calderdale, HX7 7AP

Point of connection: 398318 429563

Grid supply point: Rochdale

Energy source: Wind 240 MW

Storage capacity: 0 MW

Accepted to connect register: 240 MW 23-09-14

Target energisation date: Blank

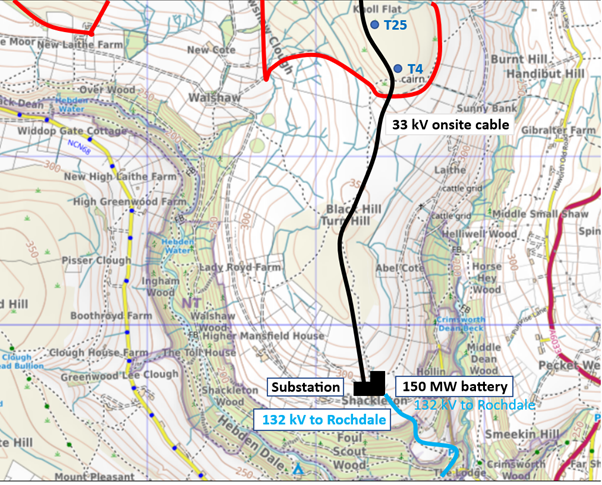

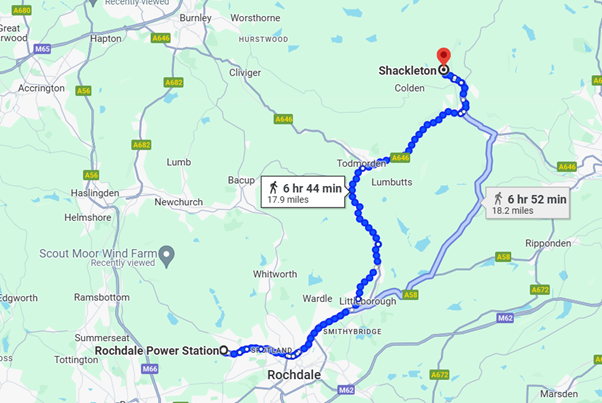

The location and postcode of the point of connection are outside the boundary of CWF, about 2 km south of T6. What3words finds it to be a building in the hamlet of Shackleton ///second.micro.reflect and Google Street View gives us a picture of the point of connection of England’s largest onshore wind farm. The onsite cabling at 33 kV will join this substation at Shackleton where it is transformed to 132 kV for transmission to Rochdale in the pair of buried cables.

The cost of such a cable was reckoned at £0.99 million/km at Brechfa Forest in 2013 and £1.2 million/km by the consultants RoadknightTaylor in 2022, but the burst of inflation since must have increased that to £1.3 million in 2024, so the cost of getting from Shackleton substation to Rochdale 132/275 kV substation is £37.4 million. It is a stiff price, and Muttley would have wanted very much to plug into the NG network at Padiham B, closer at £20.9 million and technically superior at 400 kV: “an application to National Grid has also been sought as an alternative”. It’s a strange form of words, even for Muttley.

The storage capacity entry “0 MW” might suggest that the on-site “150 MW battery” isn’t happening. This vast battery, which will cost £150 million of the £500 million budget for CWF, is the most enlightened thing in the scoping proposal, since it will smooth short term variations in output rather than piddling erratically in the direction of Rochdale like the overture and finale of a man standing at a urinal. It will do nothing for prolonged winter windlessness (the dreaded dunkelflaute) as the battery is drained in two hours. Such “externalities” are the mess that somebody else must clean up, and wind farm developers love to load them onto somebody else, but some of CWF’s “erratic flow” should be Muttley’s problem, and the expensive battery accepts it. The Register entry “Storage 0 MW” does not (I think) exclude the battery, since, like the solar panels, it is to maintain, not augment, the output. Neither battery nor solar is going to increase the 240 MW maximum power at Rochdale, so it may be correct to enter “0 MW” under Storage.

The most interesting figure in the register is the 240 MW that has been accepted for connection, which is a lot less than the 302 MW given as a maximum on the WWRE website. We can take the register at its word on 240 MW, for there are consequences if that figure is wrong either way. Muttley wants 52 turbines, not the 65 of the scoping report, and his 25% inflation is cynical manipulation of the people of Calderdale and West Yorkshire. I have heard it said, “They always do that.” Doesn’t make it any better. In the next blog I shall unpack these four cynical claims on Muttley’s website.

If I were the developer, looking after the client’s money, I would cancel today’s T56 Slack Stones, humble on its gangrenous limb, even though it will be on nobody’s hit-list. Once you see it that way, you can’t help but count exactly thirteen turbines west of Greave Clough, which has no obvious crossing for a 200-tonne crane, and notice that there are no existing tracks to its west…

I admit it has taken me sixteen blogs to abandon the western third of CWF. I had it down at first as a secondary site entrance, until Deep Stoat put me right. I thought the ample rock resource in the west would be necessary for roads until I understood the geology at T54 Bedlam Knoll and worked out that the onsite rock is no good. I’ve had the substation and battery at the western end because it was the closest on-site point to Rochdale, and I didn’t think the developers would put major infrastructure outside the planning boundary. Walking to T47 Field of the Mosses and across Crown Point Flat to T5 Grey Stone Hill showed just how deep and excellent the bog is here and how difficult it will be to ground a turbine on it. The concentration of curlew exclusion circles that we have drawn at this end is testimony to its fascination for us as explorers of CWF, but also to its uselessness as a wind farm site. All of CWF is difficult, but west of Greave Clough is hopeless, and Muttley has known this from the start.

I would not have found any of this out without visiting the sites with people who were thinking about it too.

The bodies consulted by Calderdale Council will now not be able to boast to their members, “We got it down from 65 to 52!” Those 52 turbines are exactly what Muttley has always planned to plug in at Rochdale. If the Brontë Society, the RSPB, the NT and Stronger Together can chip another thirteen off then the project becomes uneconomic. Even at 52, it will be very expensive, slow to build and horribly controversial for DESNZ. The developers will try to say, “We have conceded thirteen turbines and we are not conceding another thirteen.” But now we know that they haven’t conceded thirteen turbines, because west of Greave Clough, CWF is a Potemkin village.

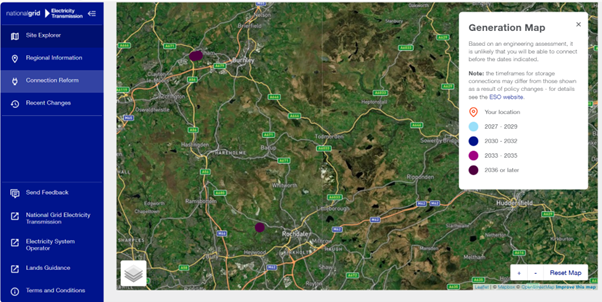

How long will it take to get CWF connected? The National Grid Electricity Transmission site has a Research Assistant for this.

It tells us that connection to the grid at Rochdale (black blob) will not be possible until “2036 or later”. It is the same news at Padiham B.

Under “Regional information” is this message for Muttley;

Rochdale – complex mesh substation, SGT reinforcement triggered already, unlikely to be able to accommodate a generator bay connection.

This may be the reason why CWF is going to be plugged into the local 235 kV system of the DNO rather than the NG 400 kV national system to which Hameldon (7.5 MW) is accepted to connect, and Scout Moor (65 MW), Coal Clough (16.8 MW) and Crook Hill (36.3 MW) are already connected. Perhaps an expert reader can unpack this point. Why are the tiny wind farms plugged in to the 400 kV, while CWF only gets the 235 kV?

“After 2036” seems a long way off, but the timetable for CWF is likely to be protracted. The RSPB think the bird work in the scoping report wasn’t up to scratch, so two more summers must be done (2024 and 2025) suggesting a planning application to Calderdale Council in 2026. I expect the council to reject by the end of 2026, and to do such a magnificent job that Calderdale Planning Department will enter the Rejection Hall of Fame, where the leading honourees have ruled too long.

- “It is impossible to sell animal stories in the USA.” (Dial Press to George Orwell)

- “Frankly my dear, I don’t give a damn.” (Rhett Butler to Scarlett O’Hara)

- “I only play with the first eleven.” (Lady Antonia Fraser to an unknown suitor).

- “We reject opportunistic Calderdale Wind Farm” (Calderdale Council Planning Department to Richard Bannister and associates)

CWF will then be called in by the DESNZ, who will read Calderdale’s rejection decision with great attention. The moment the developers have been waiting for has arrived: CWF’s future depends on Ed Miliband’s department. Cavendish Consulting are the PR wing of Muttley & co, named after the world’s most popular banana rather than the present Duke of Devonshire (or “Stoker” as Deep Stoat calls him). Cavendish say, “It’s gone from 60:40 to 80:20 following the Election”. Boosterism is the bread and butter of PR companies. I put the probabilities at 0:100 (before) and 30:70 (now) because I think DESNZ can come to understand their responsibilities to nature, and I have a much higher opinion of Ed Miliband than Cavendish Consulting evidently do.

The Muttley/Cavendish strategy depends on CWF being the first wind farm Mr Miliband calls in, and then on Mr Miliband not noticing he is the target of what his father Ralph Miliband called “a banker’s ramp” and then on Mr Miliband’s willingness to face the RSPB at full pH, whose comments at what was only scoping will … strip the paint off a pine dresser, when the developers say they have to build on the nesting birds.

If only Muttley had done the bird work properly in scoping, the whole process would have been a year earlier! As it is there may have been half-a-dozen excellent huge wind farms called in and pushed through before CWF, smutty with peat, miles from Rochdale, plonked on top of the breeding ground of red-listed birds, saturated with the floodwaters of Hebden Bridge, a limestone junkie and internationally famous as the inspiration of the Bronte sisters, sidles into DESNZ with its “Dear John” letter from Calderdale Planning Department.

That said, I had it at 50:50 until I wrote the timetable below, and realised that just as we don’t visit the sites when there are nesting birds on them, the DESNZ may prohibit building from March 31 to July 31, which would be an exquisite way for the curlews to kill the project. It must start on Cock Hill Swamp, and as I found out at T54 Bedlam Knoll, this is the liveliest bit of CWF and the easiest place for the RSPB to film bulldozers driving over skylark chicks. Is it more like 20:80? Meanwhile in Oxenhope, the residents will have parked their cars in a bit of a slalom because they don’t want the limestone trundling by for two years. Is it 10:90? For the first time since I started this project I believe the threat of intensive local action on peat, birds, limestone and Brontës will stop CWF. This is Yorkshire!

If it gets through all that, only in 2027 does CWF get hard and expensive. Because the onsite rock is known to be useless, limestone aggregate must be sourced, and there are existing customers for a rare resource, so CWF will have to join a queue. They must lease a chain of 30 tipper lorries to run continuously for two years between Horton-in-Ribblesdale and Cock Hill Swamp. The civil engineering might begin in the Spring of 2028 (D-day for the waders), and it will take two years if the weather isn’t too bad. Will building be permitted while the birds are nesting? This really is the key question, and if the answer is “No” then I don’t think CWF can be built. If the prime time of March 31 to July 31 is taken out then that will much more than double construction time because the winters can be terrible. (We love the winter on this blog! Have another look at Chris Goddard’s long run to T34 White Swamp.)

Assuming DESNZ allows radical disturbance of red-listed birds on their nests, then turbine delivery might start in Spring 2030 and it will take two years to erect the turbines, depending on the weather. (The official reason why T9 at Ovenden Moor has been broken for a year is, “It’s always too windy to fix it.”) There will be increased competition for turbines and delivery systems from onshore wind farms that are cheaper and easier to build than CWF. Although they might not be as extensive, there can be a lot of simple clusters erected on mineralised soil this side of 2030, and they will have the grid upgrade priority. Blade delivery depends either on a temporary road across the moor from Ovenden WF (obviously you can get a big turbine blade from Goole to OMWF, because there are 27 of them there already) to the CWF entrance at Cock Hill Swamp, or on bringing the blades down residential roads for an unprecedented distance from the M62 through Oxenhope. CWF is not just remote, it is moated with valleys crammed full of houses which are there precisely because the Walshaw catchment supplied plenty of water to the mills.

If everything goes swimmingly, and the imported limestone is dumped on nestlings, CWF might be able to use a connection to the grid in 2032 at the earliest, which makes “after 2036” seem less distant, and it may be that the 275 kV at Rochdale is going to be ready to receive CWF’s 240 MW earlier than 2036.

There are moves right now to reform the register. A lot of the generation presently in the queue, not least CWF, is speculative, but presently has first-come first-served rights on connection, and this speculation drives the grid reinforcement priorities. The register reforms will mean that projects don’t have priority just because they are squatting in the queue. Instead the national interest will decide where £58 billion of grid money is spent. An amusing way for Calderdale Council to stymie CWF would be to build a couple of community clusters of 50 MW in 2029 and plug them in at Rochdale. The register reforms encourage this queue jumping if CWF is looking ponderous.

Stopping developers from gaming the queue will be the easy bit. Reinforcing the transmission system to accommodate renewable generation is rife with difficulty and expense. Almost everyone in Britain, except Muttley, Cavendish Consulting and Richard Bannister, would agree that the £58 billion should be spent according to the needs of the nation and not to meet the whims of remote watershed landowners who can smell the end of driven grouse shooting. Britain needs wind power, but it doesn’t need dirty, expensive wind on remote watershed peat, and it doesn’t need CWF.

This is the 16th in a series of 65 guest blogs on each of the wind turbines which Richard Bannister plans to have erected on Walshaw Moor. Turbines 5, 6, 9, 11, 27, 32, 34, 35, 40, 43, 44, 47, 54, 58 and 64 have already been described. To see all the blogs – click here.

[registration_form]

Source link