A tool-using cow is challenging what we know about farm animal intelligence

A pet cow named Veronika uses tools in a surprisingly sophisticated way—possibly because she has been allowed to live her best life

Antonio J. Osuna Mascaró

In news that is sure to delight fans of a certain Gary Larson cartoon turned meme about the limitations of bovine cognition, cow tools are real.

Larson’s 1982 comic for his series The Far Side showed a cow standing behind a table bearing an array of oddly shaped objects. The text below the image read simply “cow tools.” Now a pet cow named Veronika has been documented not only using a tool but doing so in a surprisingly sophisticated way. The finding adds a new species to the growing list of creatures that have been found to use external objects to achieve a goal and suggests that society has been underestimating the minds of farm animals.

The story begins more than a decade ago with Witgar Wiegele, an organic farmer and traditional baker in the small Austrian town of Nötsch im Gailtal. Wiegele first observed that his family’s pet Swiss Brown cow, Veronika, would sometimes pick up sticks and use them to scratch herself, presumably to alleviate skin irritation from insects. When cognitive biologist Alice Auersperg of the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, saw a video recording of Veronika’s behavior, “it was immediately clear that this was not accidental,” she said in a statement. “This was a meaningful example of tool use in a species that is rarely considered from a cognitive perspective.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Auersperg and her colleague Antonio J. Osuna-Mascaró, a postdoctoral researcher, went to meet Veronika and her human family, who welcomed the researchers with freshly baked bread and apple strudel. “Veronika is very friendly,” says Osuna-Mascaró, who spent the summer observing her. “She also has a close bond with Witgar,” he notes. “Not only does Witgar prepare and sell bread, he also distributes it around the area. It was interesting to see Veronika watching every passing car with interest and trying to guess if the driver was Witgar. If she thought it was him, she would moo with all her might.”

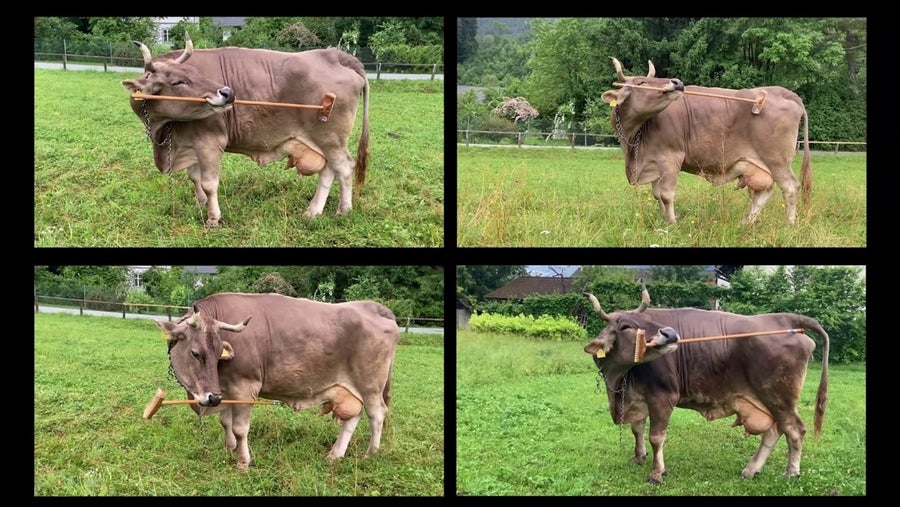

The researchers analyzed how Veronika used one particular tool—a deck brush—to scratch herself. Observing Veronika’s behavior over dozens of trials, the researchers found that she used the broom exclusively to scratch the rear half of her body, including the rump, loin, udder and belly regions that would otherwise be difficult for her to reach. She precisely manipulated the broom with her mouth, using her tongue to lift it and her teeth to secure it in place. She targeted the thick-skinned upper areas of her body with the bristled end and the more sensitive underparts with the smooth stick end. She also scrubbed more vigorously on tougher parts of her skin and used gentle pushes on her delicate parts.

To the casual observer, using a broom to scratch an itch might not seem like an act of genius. But the way Veronika changed her grip on the broom and her movement of it in anticipation of the outcome calls to mind tool-using behaviors in the famously clever primates and corvids (crows and their kin). Moreover the way she uses the two broom ends differently “”constitutes the use of a multipurpose tool, exploiting distinct properties of a single object for different functions,” Osuna-Mascaró and Auersperg write in their paper on the new findings, published today in Current Biology. Among non-human species, this kind of tool use has only been consistently documented in chimpanzees.

Such abilities may be widespread in cattle. “We don’t believe that Veronika is the Einstein of cows,” Osuna-Mascaró says. Together with anecdotal reports of tool use in cattle from South Asia, the results of the new study hint that the capacity for complex problem-solving behaviors, including tool use, might have ancient evolutionary roots but that such behaviors emerge only when conditions are favorable.

As a companion animal, Veronika, now 13 years old, has lived a long life in a stimulating environment. Nötsch im Gailtal is “the most idyllic place imaginable for an Austrian cow, like straight out of The Sound of Music,” Osuna-Mascaró says. He says the family contributed to Veronika’s tool use by “providing the special conditions that enabled Veronika to express herself.” Although she learned to use tools by herself, starting with branches that had fallen from trees, Wiegele later furnished her with sticks and rakes that allowed her to perfect her scratching techniques. Most livestock animals, in contrast, live much shorter lives and spend their time in impoverished settings such as factory farms without access to objects that they can manipulate.

Veronika uses different ends of the broom and different techniques when scratching different parts of her body.

Antonio J. Osuna Mascaró

“This is fantastic! I applaud the authors, as well as Veronika!” says primatologist Jill Pruetz of Texas State University, who was not involved in the new research. Pruetz studies how environmental factors influence the behavior of tool-using chimpanzees. She also has two companion cows of her own, Claire and Edith. “I am not completely surprised that cattle can use tools—after living in close proximity to my two cows for about seven years now, I have a lot more respect for bovine intelligence!” Pruetz says. “What strikes me about Veronika’s tool use is the precision with which she can manipulate the tool as well as switch its ends to target specific areas.”

Pruetz adds that the paper illustrates the need for enrichment for the welfare of cattle.

“There are around 1.5 billion heads of cattle in the world, and humans have lived with them for at least 10,000 years. It’s shocking that we’re only discovering this now,” Osuna-Mascaró says. “We know more about the tool use of exotic animals on remote islands than we do about the cows we live with. However, we are now starting to be sensitive enough to observe them and give, at least to a few of them, the life they deserve, one in which they have the opportunity to play, interact with objects, and discover how to use them on their own.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.

Source link