(RNS) — Jesus tells us in the Gospel of Matthew, “the poor will always be with you.” So far, sadly, he has proven to be correct. In every era, there have been marginalized people who are hungry, thirsty, homeless and in need of clothing.

As Pope Leo XIV indicated in “Dilexi te,” his Oct. 4 apostolic exhortation, Christians have an obligation to love and care for the poor. If you do not love your neighbor whom you see, you do not love God whom you do not see. The Scriptures, which admit interpretation on so many things, are clear on this point.

But concern for the poor has also been central to the church, from the early saints to its religious orders, as Leo wants us to know: “From the first centuries, the Fathers of the Church recognized in the poor a privileged way to reach God, a special way to meet him,” writes Leo. “Charity shown to those in need was not only seen as a moral virtue, but a concrete expression of faith in the incarnate Word.”

To support his argument, Leo cites Saints Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin, John Chrysostom and Augustine.

St. Ignatius of Antioch, on his way to martyrdom early in the second century, urged Christians not to be like those who oppose God, who “have no regard for love; no care for the widow, or the orphan, or the oppressed; of the bond, or of the free; of the hungry, or of the thirsty.”

Likewise, Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna (in modern Turkey) and St. Ignatius’ contemporary, urged presbyters to “be compassionate and merciful to all, bringing back those that wander, visiting all the sick, and not neglecting the widow, the orphan, or the poor, but always ‘providing for that which is becoming in the sight of God and man.’”

In defending Christians, St. Justin, who was martyred in 165, told the Roman Emperor Adrian that it is not possible to separate the worship of God from concern for the poor. During the liturgy, Justin reported, “They who are well-to-do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succors the orphans and widows, and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds, and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.”

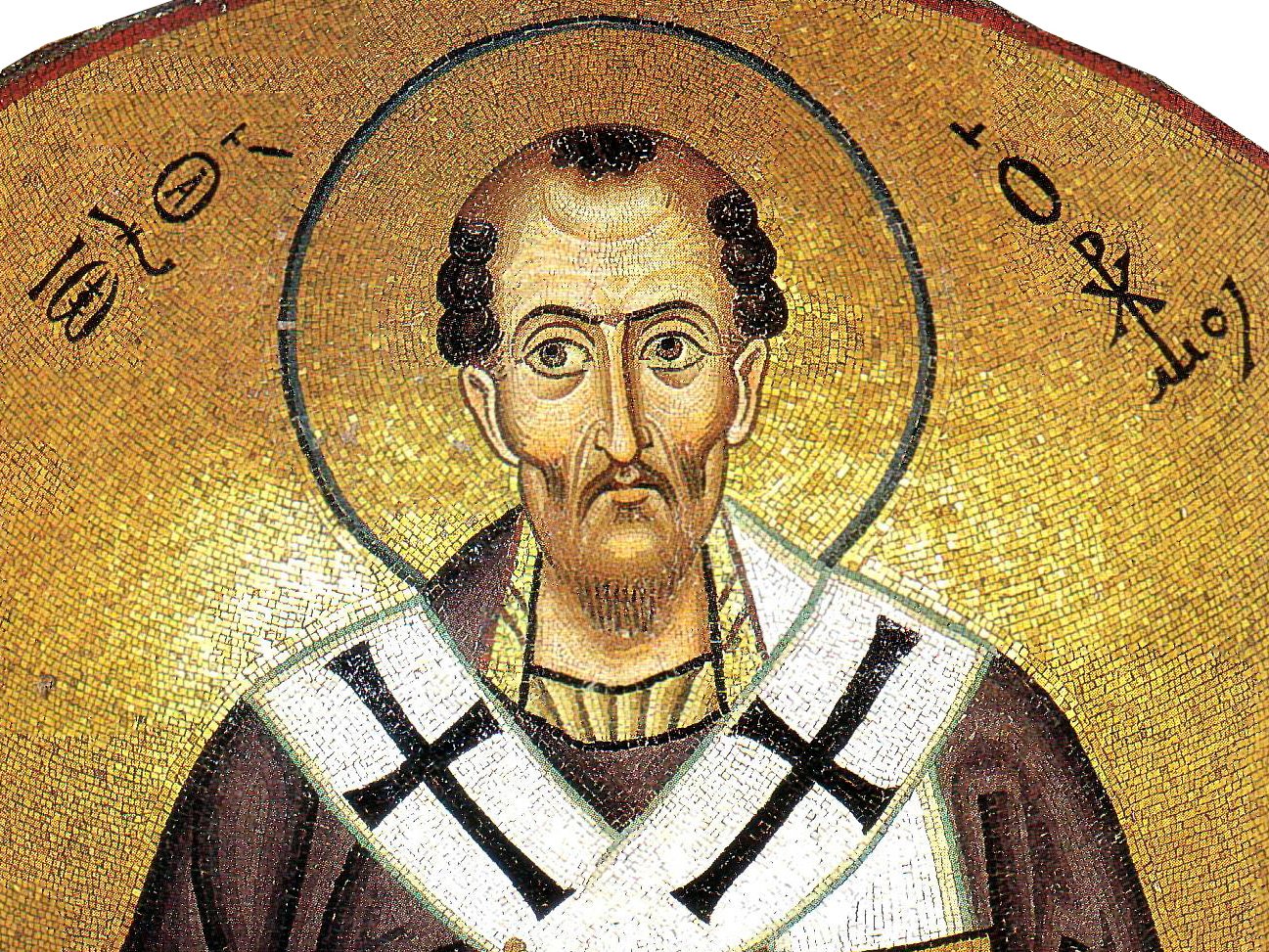

Perhaps the most strident early father of the church was St. John Chrysostom. As Christians became well-to-do at the end of the 4th century, the famous preacher fiercely attacked those who spent money on liturgical vestments but ignored the needs of the poor.

“Do you wish to honor the body of Christ?” he asked. “Do not allow it to be despised in its members, that is, in the poor, who have no clothes to cover themselves. Do not honor Christ’s body here in church with silk fabrics, while outside you neglect it when it suffers from cold and nakedness … (The body of Christ on the altar) does not need cloaks, but pure souls; while the one outside needs much care.”

He urged Christians to honor Christ as he wished. “Give him the honor he has commanded,” said Chrysostom, “and let the poor benefit from your riches. God does not need golden vessels, but golden souls.”

For Chrysostom, Christ in the poor took precedence over Christ on the altar. If he were a bishop today, he would likely spend more time and money on Catholic Charities than on the National Eucharistic Revival.

A copy of Pope Francis’ encyclical titled “Dilexit Nos,” Latin for “He Loves Us,” is shown after a press conference for its presentation at the Vatican, Thursday, Oct. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino)

In “Dilexi te,” Leo quotes him using language few bishops would use today: “It is very cold and the poor man lies in rags, dying, freezing, shivering, with an appearance and clothing that should move you. You, however, red in the face and drunk, pass by. And how do you expect God to deliver you from misfortune?”

Leo says that Chrysostom’s profound sense of social justice leads him to affirm that “not giving to the poor is stealing from them, defrauding them of their lives, because what we have belongs to them.”

Any bishop who said that today would be branded a Communist.

No major document from Leo, who led the Augustinian order of friars, would be complete without the teachings of St. Augustine, the doctor of the church born in 354. He notes that “For Augustine, the poor are not just people to be helped, but the sacramental presence of the Lord.”

According to Leo, Augustine “saw caring for the poor as concrete proof of the sincerity of faith.” Augustine teaches that God will be generous to those who are generous and that almsgiving can erase past sins.

“Fidelity to Augustine’s teachings requires not only the study of his works,” asserts Leo, “but also a readiness to live radically his call to conversion, which necessarily includes the service of charity.”

In summary, Leo concludes, “patristic theology was practical, aiming at a Church that was poor and for the poor, recalling that the Gospel is proclaimed correctly only when it impels us to touch the flesh of the least among us, and warning that doctrinal rigor without mercy is empty talk.”

That sounds very much like Pope Francis.

Leo also reviews the work of Christians who followed the example of Jesus in caring for the sick — saints such as Cyprian, John of God, Camillus de Lellis. He also mentions the religious women of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, the Hospital Sisters and the Little Sisters of Divine Providence. It was these religious who founded the first hospitals and cared for the sick, especially the sick poor, before governments and secular institutions took on the task.

“The Christian tradition of visiting the sick, washing their wounds, and comforting the afflicted is not simply a philanthropic endeavor,” teaches Leo, “but an ecclesial action through which the members of the Church ‘touch the suffering flesh of Christ.’”

“Dilexi te” also honors the monastic tradition of hospitality to the poor. “The poor were not a problem to be solved, but brothers and sisters to be welcomed,” he notes. “The monastic tradition teaches us that prayer and charity, silence and service, cells and hospitals form a single spiritual fabric. The monastery is a place of listening and action, of worship and sharing.”

Leo concludes that it is not a question of “bringing” God to the poor, “but of encountering him among them.” It is not a “gesture to be made ‘from above,’” he says, “but an encounter between equals.”

In this historical review of the church’s care for the poor, Leo reminds us of our past and our duties in the present and future. Christians have always helped the poor, but we have never done enough. Leo urges us to follow the example of the saints and recognize that care of the poor is at the heart of being a Christian. Being close to the poor, asserts Leo, was not just an “appendage,” but “an essential part of Christ’s living body.”

Source link