Hurricane Forecasters Keep Crucial Satellite Data Online after Threatened Cuts

Microwave satellite data that are key to capturing changes in a hurricane’s strength will not be taken from meteorologists as originally planned

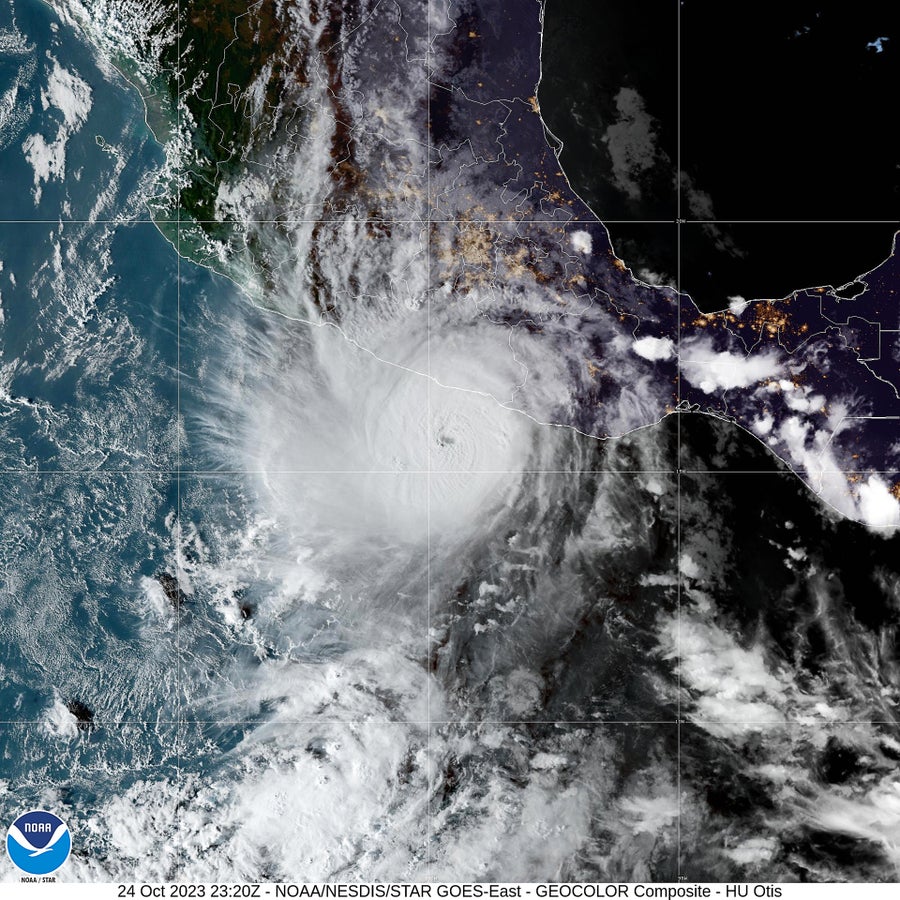

Infrared satellite imagery of Hurricane Otis compared with microwave imagery of the storm in October 2023. In the later view, the center of the storm is more visible and indicates the hurricane was strengthening. Microwave satellite imagery helped forecasters catch Otis’s strengthening before the storm made landfall.

Satellite data that are useful for weather forecasting—and particularly crucial to monitoring hurricanes—will not be cut off by the Department of Defense at the end of the month as originally planned. The data, which provide an x-ray-like view of a hurricane’s internal structure, will remain accessible to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for the satellites’ lifespans, a NOAA spokesperson confirmed in an e-mail to Scientific American.

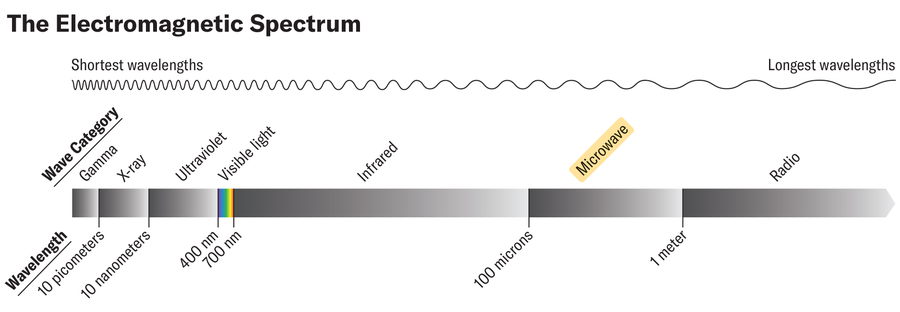

The data come from sensors onboard Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) satellites that detect the microwave portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. Microwaves are useful in monitoring hurricanes, because their long wavelengths mean they penetrate the tops of clouds, giving forecasters a view of a hurricane’s inner workings—particularly changes to its eye and eye wall (the circle of clouds that surrounds the eye and makes up the strongest part of the storm). Such changes can indicate if a hurricane is strengthening or weakening.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These data are particularly useful for monitoring storms at night, when visible satellite imagery is unavailable, and for catching rapid intensification—when a storm’s winds jump by at least 35 miles per hour in 24 hours. The faster forecasters note a storm is quickly ramping up in intensity, the faster they can warn people in harm’s way.

Because the microwaves emitted from Earth are weak, they can only be detected by satellites in very low-Earth orbit. (The geostationary satellites that provide visible imagery orbit farther out.) But satellites in these low orbits can only see small portions of the planet at a time, which means that many of them are needed to adequately monitor Earth and that there are longer time gaps between when these sensors “revisit” a given spot.

Satellite image of Hurricane Otis over Acapulco, Mexico on October 24, 2023.

NOAA/NESDIS/STAR GOES-East

Those limitations mean microwave data are already scarce. Currently six satellites provide that information for U.S. weather forecasting purposes, and they are useful for hurricane forecasting only if they serendipitously pass overhead at the right time. In June NOAA announced that data from three of these satellites would no longer be available to its scientists. The shutoff was deemed necessary because the system that processes the DMSP data is running on an operating system that is too old to update and that posed cybersecurity concerns. It is not clear why the shutoff will no longer take place as planned.

Meteorologists welcome the continued availability of the data because the Atlantic hurricane season will enter its typical period of peak activity in August. But many have expressed continued concerns about other factors that could affect forecasts and public safety, particularly staffing and budget cuts at the National Weather Service.

“While this is good news, constant uncertainty about decision-making and availability of funding, staffing, and services is a horrible way to operate,” wrote meteorologist Chris Vagasky on Bluesky. “People, companies, and governments have to be able to look ahead to know what decisions to make, and uncertainty destroys that capability.”

Source link