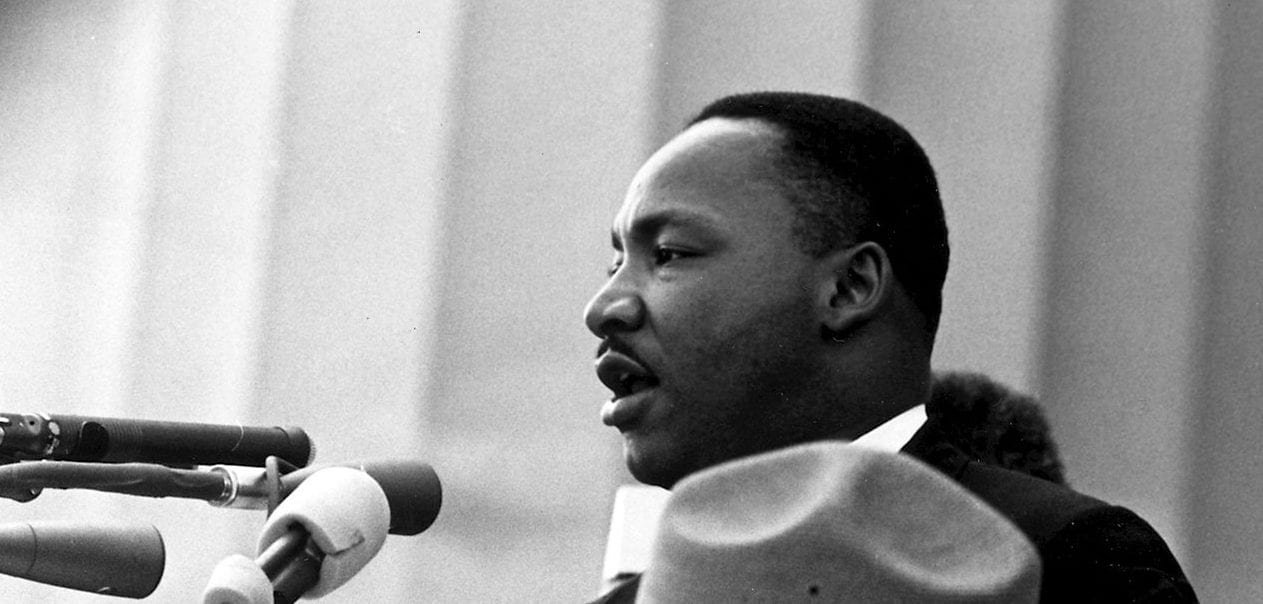

On this day, we are pleased to post this essay by Lucas Morel, Class of 1960 Professor of Ethics and Politics at Washington and Lee University and long time former faculty member at Teaching American History, who considers the lasting legacy of King’s great speech:

Equality, Fairness and Brotherhood: Common Ground for the Nation’s Diverse Citizenry

August 28th, 2013, marks the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech,” which ranks among the most famous speeches of the 20th century. Delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, King’s keynote address was heard by over a quarter million people gathered for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. King declared that the goals of the modern Civil Rights Movement were simply “to make real the promises of democracy,” which he found in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. What he called “a dream deeply rooted in the American dream” was based upon a faith, both biblical and constitutional, that “one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

With only five blacks serving in Congress, and riots mounting that summer of 1963, the 34-year-old Baptist preacher had faith that the white American majority would do right by the Constitution and their consciences. This they did, most notably by passing the Civil Rights Act the following summer and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. To be sure, a legislative full press by President (and former Senate majority leader) Lyndon B. Johnson was instrumental to their passage, pursued as a tribute to the slain President John F. Kennedy, who lobbied for a major Civil Rights bill in June 1963. But King’s televised speech kept the “citizenship rights” of black Americans on the national agenda, and thus paved the way for the passage of serious civil rights legislation for the first time in almost a hundred years.

No aspect of King’s dream has provoked more controversy than his hope that his children “will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Fifty years later, with affirmative action still debated in the highest court of the land, Americans remain divided over the relevance of race in securing equality under the law. Arguing that the Constitution should be color-blind, Chief Justice John Roberts has written that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg counters that the Constitution is “color conscious to prevent discrimination being perpetuated and to undo the effects of past discrimination.” Simply put, should race be the measure of any person’s constitutional rights?

When King spoke the language of individual, God-given rights, he found common ground for the nation’s diverse citizenry to occupy without jeopardizing any individual’s opportunity to succeed through their own work and effort. But only a year after his “I Have a Dream” speech, King doubted that in his day, true equality before the law could be achieved without “compensatory consideration” for those deprived as a result of American slavery—a category of citizens that King argued would include millions of poor whites in addition to most blacks of his day. How does one reconcile King’s devotion to human equality and individual rights with his later call for a Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged and a guaranteed annual income? His “I Have a Dream” Speech does not answer this question, but does make its appeal on the basis of traditional American principles of equality, fairness, and brotherhood. Only by respecting these did King believe Americans could “transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.”

Lucas E. Morel, Class of 1960 Professor of Ethics and Politics Washington and Lee University.