“To be a good member of your community, you really have to understand why people do the things that they do,” says Bryan Little, who teaches both on-level Government and AP Government at McPherson High School in McPherson, Kansas. “That’s why good teaching about citizenship involves students in an intentional study of human behavior.”

For Little, government class entails “constitutional study and human behavior study side by side.” Little’s study in the Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) program prompted him to think carefully about how the Constitution’s structure reflects the founders’ understanding of typical human behavior, or what they called “human nature.” Documents from the founding reveal the framers’ acute awareness that human self-interest inclines those in politics to exploit any opportunity to gain power. For this reason, as James Madison wrote in Federalist 51, the design of American government connects “the interest” of each public official to “the constitutional rights” of his office. This, Madison argued, ensures that each branch of government guards against encroachments by the other branches.

After Little’s students read an excerpt of Federalist 51, he asks them whether Madison’s view of human nature is correct. “That’s not something I would have thought to ask students before MAHG,” Little says.

Games that Reveal Human Nature

Little also uses games to prompt reflection on human behavior. “My favorite is an exercise I borrowed from a trainer ten or fifteen years ago,” he said. “It’s called “Primitive Politics.” Each student gets a stack of fake money, places $10 in a central pool, and then bids on a chance to win all the money there. Whatever a player bids is forfeited to the central pool, unless his bid is highest—in which case he wins the pool.” The game proceeds in successive rounds, with a pay-out at the end of each. “Early on, a player says, ‘I’m gonna put my whole pile in—Yay! I won!’ Then in the next round two or three of them decide to work together, gaining advantages. Players may also propose rules that players vote on—some practical, some just for revenge.” After the game ends, “we unpack the reasons why players did what they did.” Students talk about the winners’ behavior. Most succeed through communicating and cooperating well with others. Perhaps this game teaches a less pessimistic view of human behavior than Madison’s.

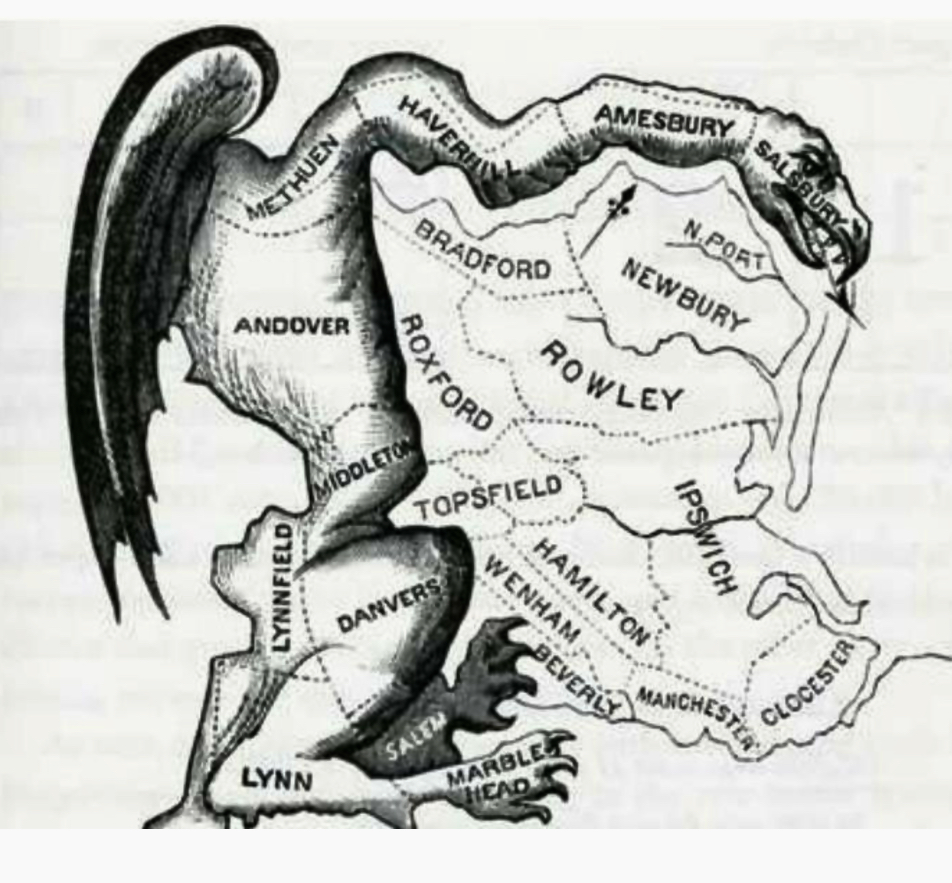

Another game would seem to confirm Madison’s view. It explores a vice in our political system—gerrymandering—that the founders did not manage to prevent. Students are assigned to either an X team or an O team, then given cards on which a series of Xs and Os are arranged in a grid. Told to draw district lines around adjacent letters, they draw reasonable boundaries at first. Little then tells them to repeat the exercise, this time designing districts that give their team as much electoral advantage as possible. They learn it is quite easy to do this. Afterwards, they examine successive iterations of the district maps for Kansas, talking about demographic data in each period that probably led party leaders to redraw the lines.

Human Nature Vs. Data Collection

Today, political pundits don’t mention the founders’ thinking about human nature when discussing Americans’ electoral choices. They talk about correlations between demographic data and voting patterns. Little pushes students to analyze demographic data “intelligently.” Political analysts use data to locate the “nudge factors” that move a group of citizens to vote one way or another. Little asks his students, “Is this correlation a coincidence? Or is there a causal relationship?”

Earlier this year he taught a lesson on political socialization. “Let’s analyze the factors that cause groups of people to trend in one political direction or the other,” he said. Students generated a list of demographic factors presumed to influence voting choices—age, gender, ethnic group, occupation, education level, religious affiliation. Little wrote the list on the board, then placed next to it laminated photos of citizens whose genders, features, dress styles, etc., suggested the demographic categories in which they fit. Students guessed the political orientation of each citizen.

“‘Then, as a last example, I put a big picture of my face on the board, and I said, ‘Okay, analyze the demographic data for this person.’

“Students said, ‘You’re an old white guy.’

“‘Okay, where does that trend?’ I asked.

“‘But you teach,’ a student said.

“‘All right,’ I said, ‘where does that trend?’

“‘Are you from Kansas?’ another asked.

“By the time we got to the end of the analysis, students said, ‘None of the data helped!’

“‘Perfect!’ I replied. ‘Data offers indicators, but it doesn’t say for sure how things are going to work. People are more than data points. They are complex animals. Their decisions are not based exclusively on their situations.”

Helping Students Discover Their Own Political Views

Little’s students find it more productive to trace the influences on their own political orientation. They take an online “political compass” test to figure out their political views. Their test results place them at various locations on a graph divided into four quadrants by two axes: one for social issues, with “libertarian” at the extreme left and “authoritarian” at the extreme right; the other for economic policy, with “left” and “right” marking the end points.

“Most years, students call out to me when the test delivers its results: ‘Sir? My test’s broken—it put me on the wrong team!’ And I reply, ‘Maybe you put yourself on the wrong team!’” This year, however, there were fewer such cases. Many students saw their results and recognized not only their accuracy but also the family and social influences that fostered their opinions. “They did some really nice, very short, but very analytical writing on where their ideologies are coming from. They were very thoughtful, maybe more so than usual.”

Why did students this fall take the self-analysis so seriously? Little speculates that the election campaign made them curious. They wondered, “Why are the adults going out of their minds over this election?” They themselves occupy less fixed positions than their elders. “They’re not entirely sure what they think or why they think it. But the election made them aware that their political views matter.”

Human Nature and Political Development

All citizens need to think not only about the sources of their own opinions; they need to think about the founders’ opinions, and how our constitutional system reflects their understanding of human behavior. “This is true for both conservatives and liberals,” Little said. “The conservative who wants to maintain the current structure of government needs to know why that structure exists. The liberal who wants to change aspects of that structure needs know why they’re not working the way they were intended to work.”

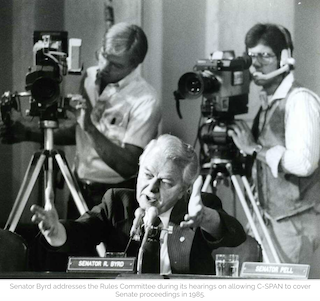

Some changes in our political system have produced results no one intended. Little recalled a Sunday evening lecture given in the MAHG residential program this past summer. Professor Joseph Postell told the history of our political party system. Parties formed even though the framers did not expect them to. The parties provided mechanisms for moderating the bills that passed in Congress and for filtering out extremist or obviously unqualified office-seekers. Electoral reforms, including the introduction of party primaries, weakened these mechanisms. Then the introduction of TV cameras in congressional chambers allowed junior legislators to subvert the authority of party leaders even further. Politics became more performative than constructive. “Postell led with the thesis that we need stronger parties,” Little recalled. “Everybody in the room—we’re all social studies teachers who feel we’re experts in history—we all thought, ‘No, that’s stupid.’ Yet by Friday, everybody was saying, ‘Yeah, he’s on to something.’”

Asked what he hoped his students understood to be the greatest threat to the continuity of self-government, Little replied, “Hopefully, us! People are the weakest part of the whole process.

“But I tell students about a book I read, Fears of a Setting Sun, by Dennis Rasmussen. He describes a feeling of pessimism that overtook the founders as they aged. They were saying to each other, ‘Well, guys, it’s been a good run. We thought self-government would work, but here we are.’ And here we still are, 250 years later.”