(RNS) — In his bestselling book “The Color of Compromise,” author and historian Jemar Tisby explored the history of racism in the American church.

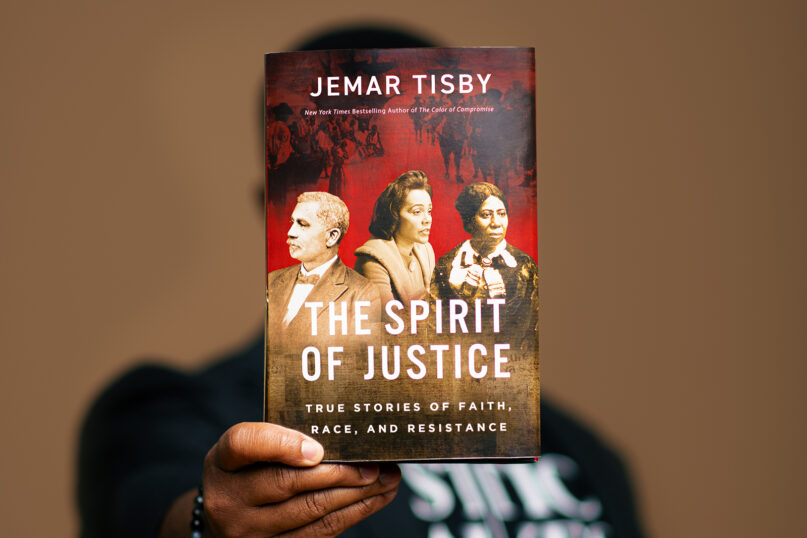

Now, in his new book, “The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance,” he looks at the other side of that history: “What about the Christians who did fight against racism?”

The book details the faith and fortitude of more than 50 people, mostly Black individuals and often women, whose stories are little known. As his research, which included the Civil War and the Civil Rights Movement, neared the present day, his book shifts to include some non-Black leaders.

“History is the study of both continuity and discontinuity,” said Tisby, who once pastored a majority white evangelical church in the Arkansas Delta and now teaches at Simmons College of Kentucky, a historically Black institution.

“So the continuity is the pursuit of justice. The discontinuity is who is involved. In the Civil Rights Movement and other eras of the Black freedom struggle, Black people were the majority. Now we’re seeing more people of other races and ethnicities partner in solidarity with the Black freedom struggle, because they know their freedom is intertwined with Black freedom. They know that right is right, and it doesn’t matter what race or ethnicity is advocating. They want to be on the side of justice.”

Tisby, who is in his 40s, talked with RNS about why he focused on lesser-known Black history figures, the roles played by wives of more well-known African American leaders, and why imagination is a virtue of justice.

RELATED: How evangelical Christian writer Jemar Tisby became a radioactive symbol of ‘wokeness’

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You write that Myrlie Evers-Williams, the widow of civil rights leader Medgar Evers, inspired you to write this book. Can you explain the circumstances that led you to that?

It was the grand opening of the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, and after the public events, she held a smaller press conference, which I was fortunate to attend, and a journalist asked her how the present-day racial justice landscape compared to the Civil Rights Movement. And she said she’s seeing things she hoped she would never see again. But then she sounded a note of hope, and she said, “It’s something about the spirit of justice.” And that phrase stuck with me. It seemed to unlock the almost incomprehensible resilience of a people who have been struggling for freedom for centuries.

Why did you choose to especially highlight mostly lesser-known figures?

Part of that was intentional. I wanted to give people exposure to a wider scope of Black Christian history. Part of that was simply where the research took me. I had to find people who not only resisted racism, but they did so because of their faith, and I had to have some historical record of that so I could include that in the book.

As you explain how the spirit of justice is seen in individuals and eras, you speak of resistance, advocacy and activism. Why do you say attending the church is an example of resistance?

The Black church in particular is a bulwark against racial bigotry. Attending church that reaffirms your humanity, that insists on your equality, is a counternarrative to the story of Black inferiority and oppression.

You describe how the Haitian Revolution was led by Toussaint Louverture, “a faithful Catholic” whose faith led him to believe descendants of Africa should have freedom. Do you see linkages between his work and the recent controversy about Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, who have been supported by some faith leaders?

Enslaved Black Haitians revolted. They won and European and white people have never let them live it down. From the time of their independence to now, they’ve faced sanctions on a geopolitical level, and also economic disinvestment, and also the stigma of racism and being labeled as Black and inferior. The Haitian Revolution and Haitian people continually stand as examples of strength and resilience in the face of oppression, but also as a sign of the backlash that inevitably comes when we resist racism.

One of the three faces on your cover is that of Anna Murray Douglass, the first wife of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, whom you describe as having regular Bible readings in their family home. What was her role in her husband’s escape from slavery?

She was integral to her husband’s escape from slavery. And in a very real sense, we may not have ever heard of a Frederick Douglass without Anna Murray. She sewed the sailor’s uniform that he used as a disguise on the train during his escape. She procured a set of freedom papers to use as a sort of fake ID in case he got stopped. And even after the actual escape, she supported him financially because he had no money. So without her, he likely wouldn’t have made it to freedom, nor been set up to become the most outspoken abolitionist of his day.

“The Spirit of Justice: True Stories of Faith, Race, and Resistance” by Jemar Tisby. (Courtesy photo)

And similarly, moving ahead in time, some might think — incorrectly — Coretta Scott King was an activist because her famous husband, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., was, but you point out that her choice of faith over fear may have, as you put it, “altered the course of the young Civil Rights Movement.” They overcame not just threats, but an actual bombing of their home and didn’t leave when they could have.

That was a critical decision, because she would have been well within her rights as a mother, as a spouse, to say, “This is too dangerous, we need to move somewhere safer.” Had she done that, Martin Luther King may not have been present and available to be the spokesperson for the Montgomery bus boycott, and we could have seen potentially a very different Civil Rights Movement. So it truly was due to her courage, particularly in that moment of physical danger and violence, to say, “No, we’re going to stay and we’re going to work for change right here.”

And then you speak of another woman with a connection to King, Prathia Hall, and the words “I have a dream.” How did the words of this daughter of a preacher end up in King’s famous speech known for those words?

She was invited to pray at a service in lament of Black churches that had been destroyed because of white terrorism. And in that prayer, she continually used the phrase “I have a dream.” A young Martin Luther King Jr. was in attendance and heard it, and afterward, walked up to her and asked her if he could incorporate the phrase “I have a dream” into some of his speeches, to which she gave her permission and did not ask for attribution. Prathia Hall herself was a force of nature, extremely passionate about justice and linked theology and activism in what she called “freedom faith.”

You close your book citing four virtues of those who pursue the spirit of justice. One of them is imagination. Why did you name that as a virtue, and what do you imagine ahead for yourself as you pursue spiritual justice?

Oppression suppresses our ability to dream. We are stuck in survival mode, and it becomes hard to envision a different reality. But that is precisely what is needed in pursuit of justice, because we have to imagine a different world, and we have to picture what that might be. Fundamentally, that phrase “I have a dream” is about a theological imagination for what a society filled with justice and peace might look like.

I have a burden to continually remind people that we should be learning from the Black Christian tradition. Whatever is coming next, we will do well to gain wisdom and knowledge from what Black Christians have experienced and gone through before us. And that’s not easy in a society that considers Black church, Black theology, inferior to European or white expressions.

Does that mean you’ll keep preaching in your own way?

(laughs) My line between preaching and teaching is very thin whenever I speak.

RELATED: Will my book be banned?

Source link