(RNS) — In sanctuaries across the United States on Sunday morning (Sept. 1), unionized workers will stand behind pulpits and contend that God is on the side of the labor movement. They believe this because the Bible tells them so. Both the Old and New Testaments are replete with warnings to those who exploit workers, and no less than Jesus himself once declared, as the Gospel of Luke reports, “the laborer is worthy of his hire.”

These worker-preachers will carry on the tradition of “Labor Sunday.” In it its early 20th century origins, it was a tangible sign of growing friendship between Christian churches and the labor movement. Church and labor had often squared off in freewheeling Gilded Age fights over the morality of industrial capitalism, but leaders from both sides, recognizing they would be stronger together, worked to bridge the divide.

Labor Sunday was one concrete outgrowth of their efforts. Each year, on the Sunday before Labor Day, churches across a wide array of denominations would infuse their worship services with hymns and prayers that emphasized economic justice.

The most convicting moments often came when a glove maker or blacksmith stood before the congregation and shared candidly about how their faith propelled them into the labor movement. This annual observance was one small way that church and labor partnered to nurture a social gospel faith that insisted on the sinfulness of structural inequality.

Seeds sown in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era went on to bear remarkable fruit. Throughout the mid-20th century, progressive Christian faith shaped moral intuitions at the grassroots and at the highest echelons of American government. Leaders steeped in social gospels were among the architects and inspirations for the New Deal.

Frances Perkins, secretary of labor for 12 years under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the first woman to serve in the U.S. Cabinet, was a devout Episcopalian who helped secure the passage of the landmark Social Security and Wagner acts. Monsignor John Ryan devoted his career to popularizing the Catholic notion of a “living wage” — first outlined in Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical, “Rerum Novarum” — and became known as “The Right Reverend New Dealer” after endorsing FDR in 1936.

Decades later, Cesar Chavez often cited that very same encyclical in contending for the moral legitimacy of farmworkers’ organizing efforts in California’s Central Valley. Meanwhile, in the final month of his life, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. brought striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, to their feet, riffing prophetically on the parable of the rich man and Lazarus.

Over the course of the last generation, however, this tradition lost both steam and cachet. Between the rise of the religious right, with its surging gospel of free enterprise, and unions’ struggle to retain any kind of traction in the private sector, social Christianity’s profound influence on an earlier moment in the nation’s life was easy to forget. When Labor Sunday was remembered at all, it seemed almost quaint.

But evidence abounds that we may be living through a revival of this old-time religion. Far from genuflecting to a past golden age, the workers who stand behind pulpits today will fan the flames of a social gospel tradition that changed the nation once — and may just be poised to do it again.

It was one thing when radical Christians bearing placards that read “Blessed are the poor” surfaced in New York City’s Zuccotti Park at the height of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Their insistence that “Jesus stood with the 99%” certainly hearkened back to the heyday of the social gospel. But while that rhetorical flourish had some durability, the movement itself did not.

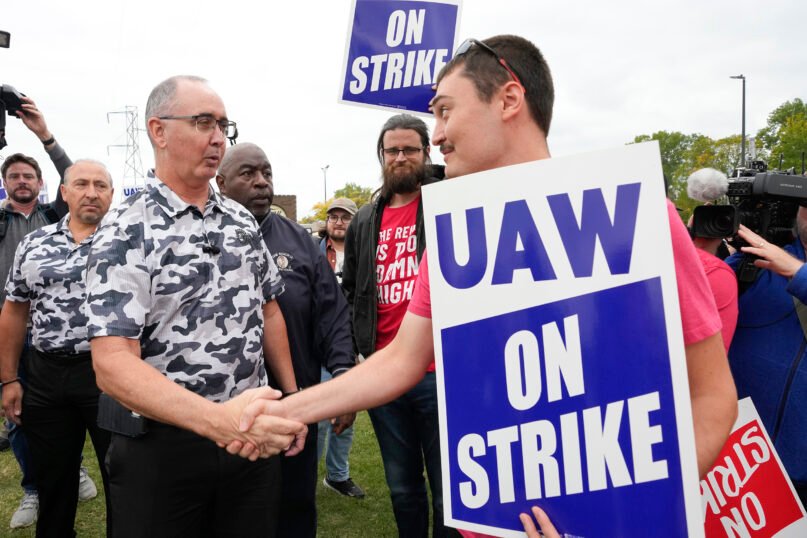

It was quite another when Shawn Fain, president of the United Auto Workers, started quoting passages from his grandmother’s Bible during the UAW’s stand-up strike last fall. On the eve of the strike Fain cast the battle ahead as a “righteous fight.” He went on to offer an interpretation of the passage in Matthew’s Gospel in which Jesus vows, “It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God.”

Fain declared, “Why is it easier to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God? I have to believe that answer, at least in part, is because in the Kingdom of God, no one hoards all the wealth while everybody else suffers and starves. In the Kingdom of God no one puts themselves in a position of total domination over the entire community. In the Kingdom of God no one forces others to perform endless, backbreaking work just to feed their families or put a roof over their heads. That world is not the Kingdom of God. That world is hell.”

Fain’s sermon struck a chord with the UAW faithful, who went on to win landmark concessions in their tussle with the Big Three automakers. In the months since, he has kept preaching and the union has continued to notch improbable victories.

The UAW’s success at unionizing a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, this past spring is particularly interesting in terms of what it augurs for the future of pro-labor faith. The South has always been rocky soil for unions. Even at the height of the 20th-century social gospel, organizers found that — in the Bible Belt of all places — Christianity was more often an obstacle than an asset to their work. As historians Elizabeth and Ken Fones-Wolf have shown, the Congress of Industrial Organizations’ massive postwar Operation Dixie campaign floundered in no small part thanks to concerted white evangelical resistance.

It was all the more notable, therefore, that at the celebration after the UAW’s historic win at Chattanooga, Fain went right back to the Bible, again quoting Matthew: “For truly I tell you, if you have faith the size of a mustard seed, you will say to this mountain, move from here to there, and it will move; and nothing will be impossible for you.”

He told The Guardian afterward, “I’ll continue to lean on my faith. I don’t keep that any secret.”

The revival Fain is leading may not remain a secret for long. White Christian nationalism continues to dominate the headlines for the time being, but those who are hoping for the rise of a “modern social gospel” may be in luck. Worker-preachers are back on the move and not just on Labor Sunday.

(Heath W. Carter is associate professor of American Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Source link