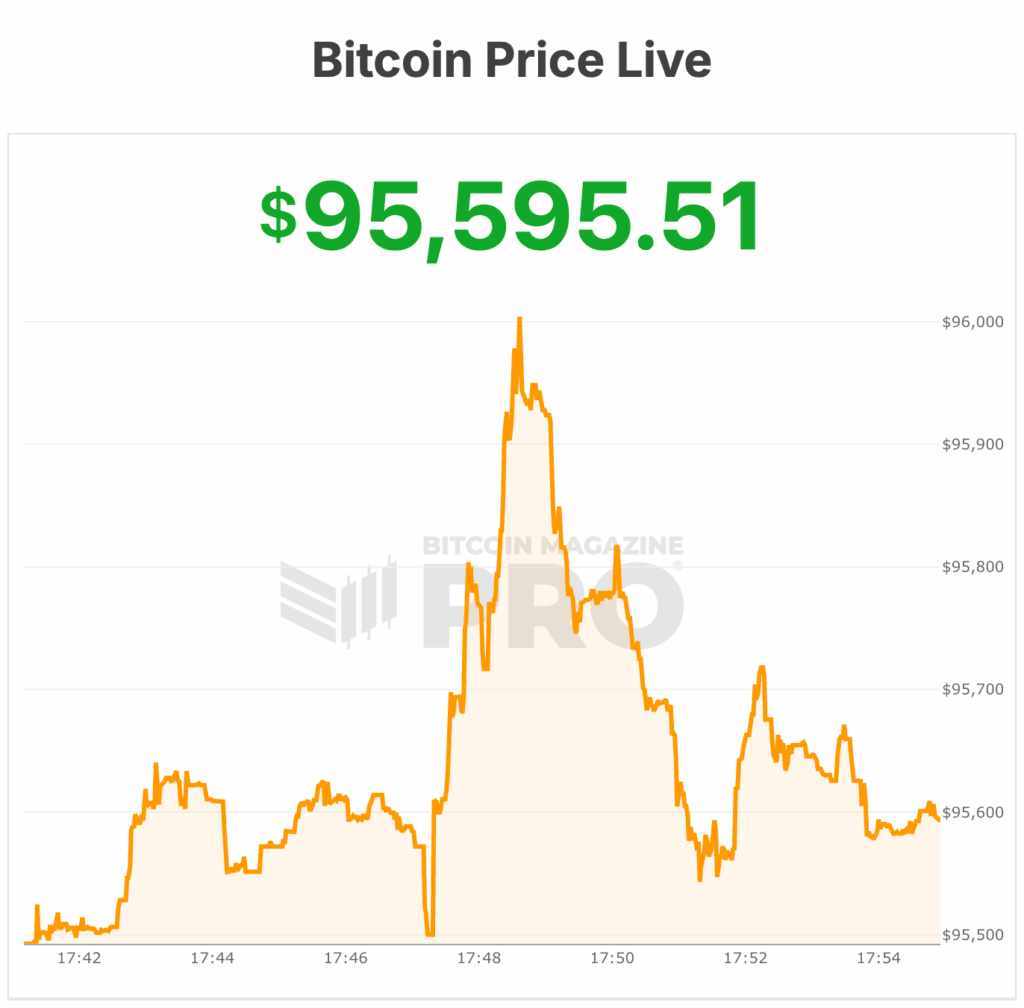

The Bitcoin price surged through the $96,000 level this afternoon, pushing decisively above a key resistance zone and signaling a renewed wave of bullish momentum after weeks of choppy, range-bound trading.

At the time of writing, the bitcoin price is trading around $96,000 up roughly 4.4% over the past 24 hours, according to market data.

The breakout marks a clear move beyond the upper boundary of January’s consolidation range. Bitcoin price is now hovering near its weekly highs, sitting approximately 5% above its seven-day low near $91,700, as buyers regain control of short-term market structure.

All this is happening as the US Senate Agriculture Committee has delayed its key markup of the Digital Asset Market Structure CLARITY Act until late January. The Senate’s Banking Committee markup is still scheduled for January 15.

Senate Agriculture Committee Chairman John Boozman announced a timeline for advancing crypto market structure legislation, with legislative text set for release by the close of business on Wednesday, January 21, and a committee markup scheduled for Tuesday, January 27, at 3 p.m.

Boozman said the schedule is designed to ensure transparency and thorough review while providing regulatory clarity for crypto markets and supporting consumer protection and U.S. innovation.

The delay signals that Senate leaders may lack the votes to advance the bill amid disagreements over stablecoin rewards, DeFi oversight, and SEC–CFTC authority.

Although the House passed its version in mid-2025, the bill cannot move forward unless both Senate committees approve it.

Despite this, Bitcoin trading activity is rallying alongside the price rally, with 24-hour volume climbing to roughly $55 billion, reflecting renewed participation as price accelerated higher.

Bitcoin’s total market capitalization has risen to approximately $1.92 trillion, reinforcing its dominance within the digital asset market. Circulating supply currently stands at just under 19.98 million BTC, inching closer to the protocol’s fixed 21 million coin cap.

Strategy ($MSTR) stock soars

Shares of Strategy (MSTR) jumped sharply today as well, closing at $172.99 USD with a 6.63% gain today and extending strength in after-hours trading up to $177.00, up +2 after hours, as investors continue to price in the company’s high-risk, bitcoin-linked strategy.

On January 12, Strategy announced they added 13,627 bitcoin for $1.25 billion, lifting its total holdings to 687,410 BTC.

The purchases were made between January 5 and January 11 and funded through the company’s at-the-market offering program, which included sales of Class A common stock (MSTR) and its 10.00% Series A perpetual preferred stock, Stretch (STRC).

Bitcoin price outlook

Tuesday’s surge follows several failed breakout attempts over the last couple of months, when bitcoin repeatedly tested resistance near the mid-$94,000 range before pulling back.

For much of the past month, price action remained compressed between roughly $85,000 and $94,000, prompting analysts to warn that bulls needed a decisive move higher to reassert control. That move now appears to be underway.

If the bitcoin price can sustain acceptance above $96,000, the next major resistance zones sit between $98,000 and $104,000, levels that previously capped upside momentum. A failure to hold current levels, however, could see price retrace toward former resistance turned potential support.

The breakout arrives as investors continue to weigh inflation trends, interest-rate expectations, and escalating political uncertainty tied to U.S. monetary policy.

On the political side, the Department of Justice has opened a criminal investigation into Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. The investigation is intensifying a months‑long feud between the White House and the U.S. central bank

According to Powell, the DOJ served the Federal Reserve with grand jury subpoenas and threatened a criminal indictment tied to his June 2025 testimony about a $2.5 billion plus renovation of Fed office buildings.

In recent months, the bitcoin price has increasingly traded in response to macro narratives, with many participants viewing it as a hedge against policy instability and long-term currency debasement.

At the time of publication, the bitcoin price is near $96,000.

Source link