Video: Amir Campbell

Portrait photographer Ronald Gray began working with cameras as a teenager, as a lighting and equipment “lab rat” for his father, who worked as a wedding photographer on weekends and a Philadelphia police officer during the week.

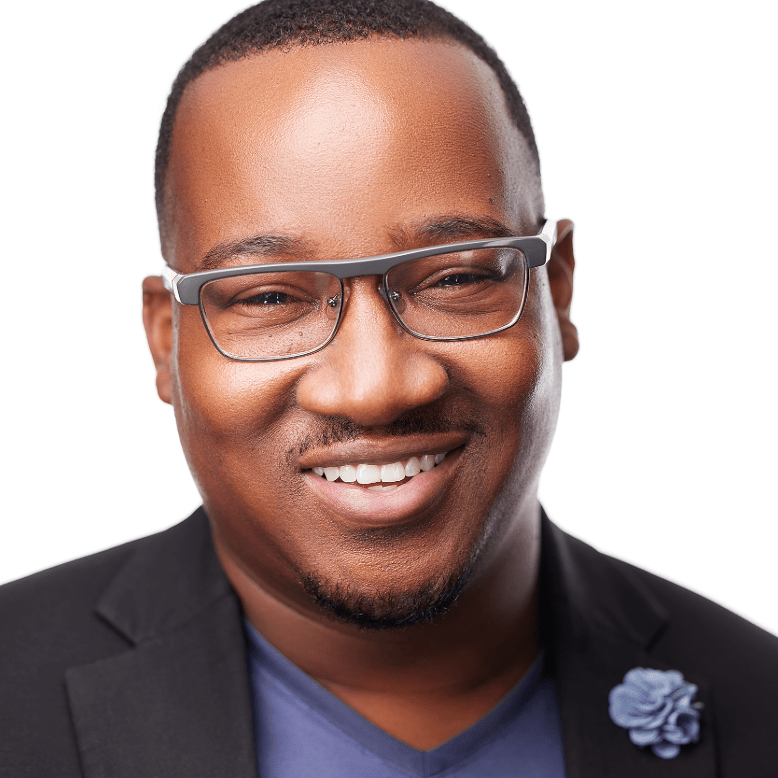

Photographer Ronald Gray Photo: Peter Hurley

Now an award-winning photojournalist—and a photographer for the Philadelphia Police Department’s audiovisual unit—Gray, 44, has captured a wide spectrum of the human experience behind his lens: from protests and funerals to weddings and maternity shoots. Photography, he says, is a way of “letting people know that you lived, and letting people know that you mattered. It outlives all of us.”

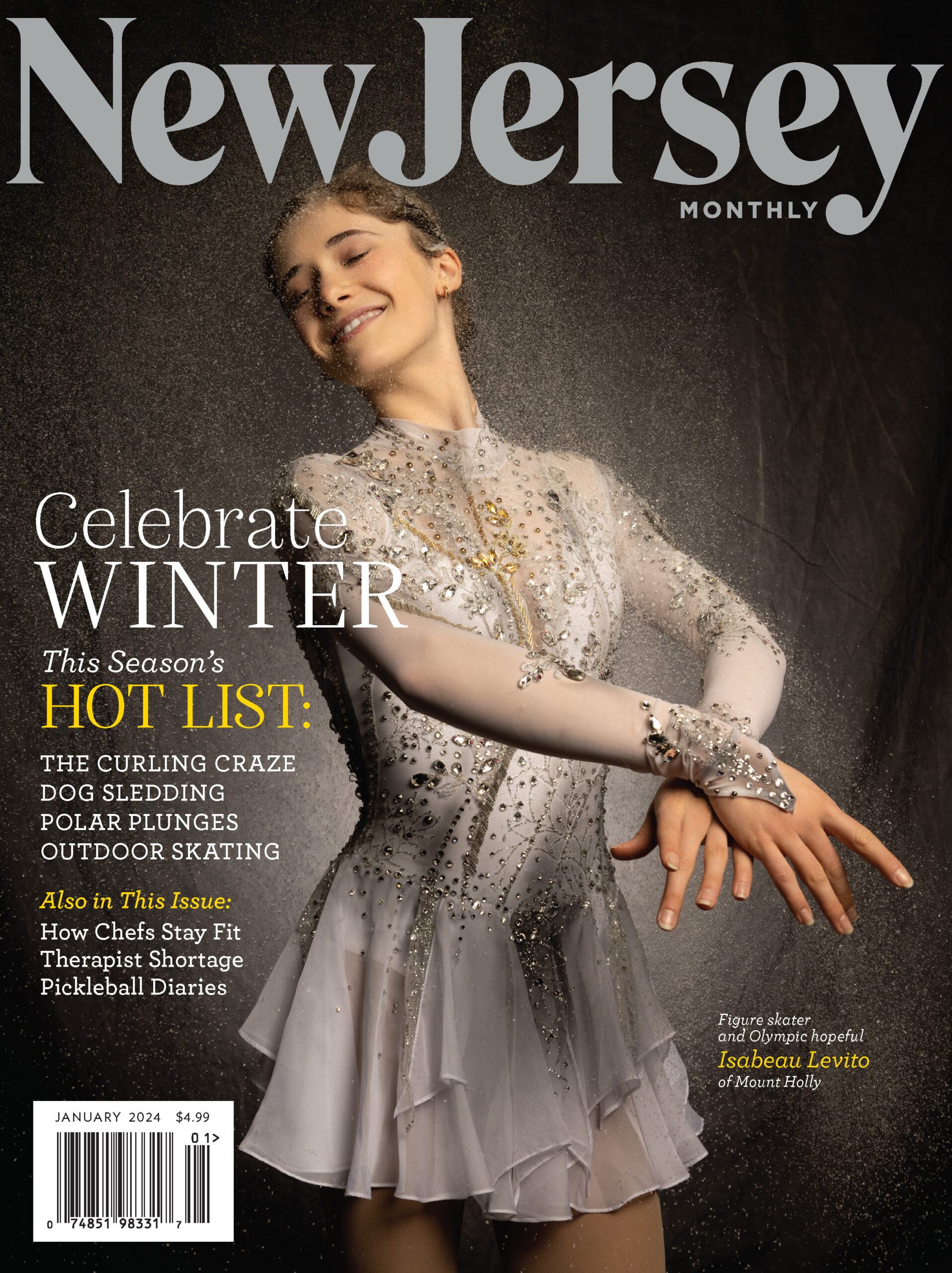

Gray shot New Jersey Monthly’s January cover star, Mount Holly figure-skating phenomenon Isabeau Levito, at the Igloo at Mt. Laurel. Though he snapped plenty of photos of her on the ice, the winning shot was captured in a back room as videographer Amir Campbell tossed fake snow around—”getting it in all of our eyes!” Gray jokes.

Read more about Gray’s process below.

Photographer Ronald Gray and videographer Amir Campbell capture figure-skating star Isabeau Levito for New Jersey Monthly’s January issue at the Igloo at Mt. Laurel. Photo: Andrea Hunter

Was this your first time shooting on ice?

Yes. The ice is very slippery—you kinda have to take those, like, little shuffle baby steps. Me, I was making light of it—I was telling Isabeau: If I fall, don’t laugh at me. But it was cool. I love the challenge. I love doing stuff that’s different, things that I’ve never done before. It’s cool—and it worked out really well.

NJM’s art director Gail Ghezzi explained to me that one of her main impressions of your work was that you’re very skilled at bringing out the human quality of subjects—that there’s not a disconnect between your subjects and the person looking at your photos. How do you typically prepare for a shoot?

I just try to make sure that we’re all on the same page. I try to get an idea of what subjects intend to wear, what they look like. I don’t want to necessarily hide flaws—I want to maximize strengths. Because we all have flaws and things that we might feel, you know, a little strange about as far as our looks. Some people have a preference for a particular side, things like that. But I just try to bring out a little bit of them.

And I try to find out something about them beforehand if I can. I didn’t really know anything about Isabeau, and I had never done anything for a professional skater before. I remember I Googled her, and a couple of YouTube videos came up. I wanted to know what she looked like; I was curious. Then I actually watched her routine. You hear about her age, and you’re like, Oh, she’s so young. But then when you see her skate, you’re like, Wow. And I was curious—I had so many questions about skating. She was a very, very, very bright young lady. I learned a lot.

Photo: Ronald Gray

Our art director Gail also noted that you don’t aim for absolute perfection in your work; that a viewer can see unique little flaws on your subjects—hair that isn’t perfectly in place, skin that isn’t utterly uniform. That attention to detail and texture, Gail explained, creates an ultra-human quality in your photos. You often work with makeup artists on your shoots—is there anything specific that you instruct them to do or not do in this regard?

With Isabeau, the one thing I didn’t want—and I know Gail also didn’t want—was for her to be too glammed up. We wanted her to actually look her age, and I just didn’t want to be too heavy-handed with the makeup. And that was it.

Pretty much 90 percent of the stuff you see in my portfolio, my makeup artist, Andrea Hunter, has done. She’ll often have a conversation with the client and say, Okay, what do you have in mind? And sometimes I’ll tell clients: Bring a picture. If you were inspired by something and you want to replicate that, bring that. Andrea has the experience and that artistic eye, too, so it works.

Buy our January 2024 issue here. Cover photo: Ronald Gray

Is that textured, human quality something you are consciously striving for, or is it more a natural result of your lighting and/or process?

It kinda flows naturally. It’s a product of lighting—it all starts with the lighting. There is retouching that’s done on the image, but you don’t want to overdo it. You want the skin to retain texture in the final images. You don’t want a person to be completely smoothed out and look like they’re made of porcelain. That’s important to me.

In addition to editorial and commercial shoots, you’ve done a lot of work in the photojournalism realm. When you’re covering something like a protest, you’re not engaging in drawn-out artistic collaborations; you’re quickly documenting moments that are unfolding in real time. Does that ever make photojournalism feel like less of a quote-unquote creative endeavor? Or does its heightened nature allow you to capture something different?

Yeah, I think it does, because it’s like—you have to have the ability to see something happening before it happens. And I don’t know if I would call that creativity, or moreso just good timing, but it’s a little bit of everything, too. And it’s working certain angles. Because if something crazy is happening—you have a bunch of photographers there, a bunch of people with cameras—you’re all shooting the same thing. But when you see the final results, the images can look completely different. So sometimes that creative part comes in from switching the angle to low when everybody else is shooting high. Getting closer when everyone else is shooting far back. Shooting wide when everybody else is shooting tight.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.